Is Tetractys Theory the Best Explanation of Why the Cormoran Strike Series is Ten Books in Length?

First Thoughts on Evan Willis' Numerological Exegesis of Rowling's Two Ten Novel Series and the Meaning of This Structure

I pledged two weeks ago that my next post here would be about the virtue of Prudence and the possible meaning of a character named ‘Prudence’ appearing in the opening of Running Grave as Charity did in Deathly Hallows. I’m still committed to writing that piece but Evan Willis’ explanation of ‘Why the Cormoran Strike Novels are a Ten Book Series’ that was published here Monday before last is so wonderfully engaging and challenging that I feel obliged to write about it first.

In brief, what Willis has attempted here (and largely succeeded in doing I think) is to create a synthesis-theory out of the various elements Serious Strikers and Rowling Readers have noted in the author’s various novels and two series of books, namely, the backdrop myths, literary alchemy, hermetic symbolism, ring structures, parallel series theory, even the I Ching and tarot divination. He introduces Pythagorean numerology as the glue that makes these varied elements all stick together in a lucid explanation of why the Strike series is ten books rather than seven books in length, and, along the way, the relationship of Rowling’s three extra-series, supposedly stand-alone novels — Casual Vacancy, The Ickabog, and The Christmas Pig — have with her Potter novels. Valid or not, Willis’ theory swings for the fences and deserves the immediate and prolonged attention of every reader following Rowling’s work; if he is right, frankly, he has managed to find the structural and symbolic key in medias res that opens up her artistry and meaning, an accomplishment anticipatory of scholarship that would usually only be discovered many years post mortem auctoris.

But is he right? If you’re like me, the history and meaning of the tetractys, a ten point pyramid structure, was something totally new and, in that novelty, sufficiently strange and unfamiliar to seem unlikely as Rowling’s story-scaffolding for the Strike series, the Hogwarts Saga, and her other solo work (excluding only the Cursed Child script and the Fantastic Beasts screenplays). Today I want to look at Willis’ theory to explore briefly the history of numerology in literary criticism, the verifiability of Tetractys theory, my quibbles with Monday’s first explanation of it, what his synthesis-hypothesis means if true about Rowling’s planning of her work, an alternative geometrical symbolism for the Strike series being ten books in length, and the ‘So What?’ of it all, what it tells us about the author’s core meaning and aim in writing. I can only touch on these subjects, of course, but each point I think is important to even begin to gain an appreciation of what Willis has attempted and perhaps achieved in his post.

None of this, of course, will make sense if you haven’t read Willis’ ‘Why the Cormoran Strike Novels are a Ten Book Series’ so please do that if you haven’t already.

Numerological Literary Criticism

Willis in an already long post did not take the time or space necessary to introduce the idea of Pythagorean numerology as a method employed by literary critics to explain the structural artistry of Great Writers. That subject deserves a long post of its own and even a cursory introduction to the subject in Monday’s piece, though it might have made Tetractys theory seem less of a stretch than it must to readers unfamiliar with this approach, would have dissipated the concentration of his presentation.

It’s helpful, though, I think, to see that Willis’ approach has important critical precedent; the man isn’t coming out of left field with a bizarro geometrical explanation just because, as a teacher of geometry, that is the single-tool hammer he has at hand.

Think of literary alchemy. When I first argued in 2002 that Rowling was using the symbolism and color sequences of metallurgical alchemy in her Potter novels, I was unaware of the critical tools then available to make this argument, most notably, Lyndy Abraham’s Dictionary and Stanton Linden’s Darke Hieroglyphicks (my references were to Burckhardt, Lings, and Eliade). I was dismissed by Alan Jacobs as something of a ‘Code Breaker’ quack, an opinion that remained the rule, alas, until I engaged the historical precedent and methodology described by Abraham, Linden, and others (the discovery of Rowling’s 1998 “I always wanted to be an alchemist” comments in 2007 didn’t hurt, either). Anyone who denies the hermetic content of Rowling’s work is now the Oblivious Outlier rather than Academic Authority.

Rowling’s use of mythology as the backdrop templates of her stories, too, was something of a stretch, despite her background in ‘Classical Studies,’ a concentration heavy on myth and light on Greek and Latin language work. The Orestes-Potter scar, the Theseus and the Minotaur shades in the first Fantastic Beasts film, and the Leda, Swan, Castor, Pollux, Eros, and Psyche coloration and characters in the Strike novels make a lot more sense and are more credible when a reader is familiar with C. S. Lewis’ retelling of the Eros and Psyche myth in Til We Have Faces, James Joyce’s retelling of the Odyssey within his Ulysses, and the exegetical work of Freud and Jung (and their legion of disciples) with myths that explain them as psychological psychomachia.

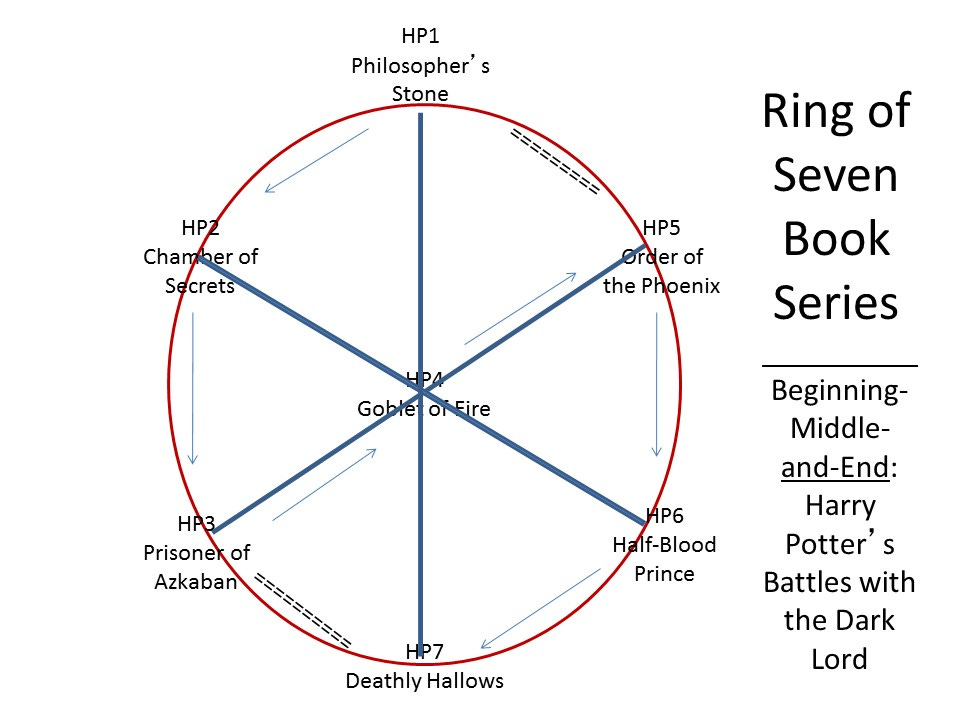

And ring composition? As much as this is currently a ‘given’ in Rowling Studies, without the testimony of anthropologist Mary Douglas in her capstone Thinking in Circles about this traditional story scaffolding, who would have taken my argument seriously way back in 2010? To be honest, I doubt very much that I would have seen the structure in the Potter novels and series without having read in Sanford Schwartz’ C. S. Lewis on the Final Frontier about Douglas’ contention and then read Thinking in Circles myself. Brett Kendall had already discussed the chiastic structure of the series — in 2003 post Phoenix! — but I didn’t ‘get it.’ More on Kendall in a second.

It helps, then, when trying to grasp a new idea in literary criticism to know that it’s not something the exegete has made up whole cloth but an idea with significant precedent, i.e., that the ‘new’ idea is only ‘new’ to the reader. This is the case with the use of Pythagorean numerology by authors and by subsequent critics attempting to understand their work. The key name in this case, a la Abraham, Freud, and Douglas, is Alastair Fowler and the single most important book his Triumphal Forms: Structural Patterns in Elizabethan Poetry.

If Fowler’s name is familiar to readers of HogwartsProfessor, it is because his work has been referenced repeatedly in posts there, mostly in reference to chiastic writing, but also with respect to the use of Cratylic Names and astrological symbolism in English literature; he literally ‘wrote the book’ on these subjects (cf. Literary Names and Time’s Purpled Masquers) and remains the ‘Go To’ starting-point academic reference in Milton, Spenser, and Lewis studies.

Triumphal Forms, though, is the relevant work here because it is Fowler’s primary effort in demonstrating the use of Pythagorean numerology in understanding the work of the ‘Greats.’ The back cover of Forms spells this out:

[Forms is a] study of numerology in Elizabethan poetry, with some background studies which base the subject in classical learning, the works of Dante and Petrarch, and the esoteric traditions of the humanists. The central assumption of numerological criticism is that there exist works written in this tradition which show a correspondence between structure and meaning on a numerical plane; that is, one in which the number of the constituent parts (lines, stanzas, sonnets in a sequence) expresses a major aspect of the meaning. For instance parts of the whole can be arranged to represent months of the year and so on. Such structures of time and the triumphal form, in which the most important 'sovereign' element is placed at the centre, are the two main numerological patterns discussed by Dr Fowler.

Critics have tended to regard numerology as an isolated phenomenon, rare after the Middle Ages but Dr Fowler demonstrates its persistence in the works of Spenser, Sidney, Chapman, Shakespeare, Donne, Jonson, Dryden and others. He suggests that Elizabethan sonnet sequences (including Shakespeare’s) should be regarded as long stanzaic poems of complex numerological structure.

That last note about Shakespeare’s sonnets is especially relevant here because it is the apex and most challenging piece of Fowler’s argument in Forms, namely, that the 153 sonnets are best read in “Pythagorean fashion,” an extended form of the “great quaternion” or tetractys, “an equilateral triangle with a base of 17” (185, discussion 174-197). Fowler earlier in Forms had discussed the use of the tetractys itself as the symbolic structure of Dryden’s 10 stanza Ode to the Memory of Mistress Anne Killigrew (112-118). For those waiting on Rowling to use Shakespeare’s Sonnets as the source of a Strike novel’s epigraphs, take heart (if not an Ink Black heart). Per Evan Willis’ theory, perhaps that will be the source for the pinnacle tetractys book in the series, Strike 10, the ultimate hat-tip to the greatest of literary alchemists, psychomachian allegorists, and numerological wizards.

Fowler’s demonstration of the value of Pythagorean numerology in understanding the structural choices establishes the critical precedent for Willis’ usage. Perhaps as important, it dispels the idea that Willis only sees the tetractys because he is a geometry teacher. If anything, Willis was uniquely positioned to grasp this because of his familiarity with sacred geometry.

Brett Kendall, who I mentioned earlier, was the first to see the chiastic structure of the Potter novels a a series, the only person who grasped this and one who saw it four years before the finale was published. As he explained it to me, this was possible, even inevitable, because of his day job as a graduate student and adjunct instructor in Old Testament studies at Fordham University. Chiasmus, he told me, is the baseline foundation of all reading in this field; it was hard for him not to see what he saw, if it remained all but impossible to make out for the hundreds of millions of readers not looking through those spectacles.

And so also with Evan Willis.

Having established that a teractys reading is not the product of a reader’s frenetic imaginings but a critical lens with significant precedent and authority via Alastair Fowler, let’s move on to a look at the theory’s verifiability.

The Predictions of Tetractys Theory

The mythic templates, literary alchemy, ring composition, and parallel series theory have all been invaluable in after-the-fact discussion of the Cormoran Strike novels. As tools for prediction, though, outside of Louise Freeman’s hit on the Olympic Games as backdrop to Lethal White and Evan Willis’ seeing who killed the Minister official in the same book, the game of picking up Rowling’s twitter-header breadcrumb picture-clues, as demeaning as that is frankly and non-literary, has been much more useful than our critical lenses for divinatory purposes.

Willis’ Tetractys idea in contrast to the several elements mentioned above, all of which he has brought together in a synthetic Grand Unifying theory, comes complete with Pass or Fail predictions of what Running Grave will be about, the nature of the last three books in the ten book series, as well as about the meaning of the series as a whole. We’ll know, in other words, by the end of September if Tetractys Theory is right or wrong, at least with respect to its Running Grave portion.

The heart of Willis’ idea, if I understand it correctly, is that both of the mythological templates Rowling-Galbraith has in play for the Strike series, Castor and Pollux a la ‘Leda and the Swan’ and Eros and Psyche, include before their endings a division of the pairs; Castor and Pollux are separated by Zeus to the stars and Hades only to resurface at the trial of Orestes while Eros and Psyche are separated because of Psyche’s injuring Eros with oil and light, a divorce only reconciled on Olympus after Psyche survives a series of Venereal trials. Willis predicts, consequently, that Cormoran and Robin will be separated at the end of Running Grave via a political crisis akin to the Trojan War’s place in Greek mythology, a personal or global earthquake occasioned by revelations about the death of Leda Strike, and that the Agency Partners will only be reunited in the tenth book in efforts to rescue nephew Jack, in parallel with Christmas Pig and in alignment with the Orestes court case.

Not good news for all those Strike fans longing for romance but, for Serious Strikers as intrigued by Willis’ theory as I am, this makes the anticipated publication of Running Grave that much more exciting. In addition to fun Deathly Hallows parallels which are rolled into Tetractys Theory as essential, Strike7 will be a nigredo capstone that divides Robin and Cormoran for the next two books. Willis’ chips are all on the table for this next book, and, whatever your thoughts or feelings about Tectractys Theory, you have to admire the chutzpah involved here.

Quibbles, Objections, and the Elephant in the Reading Room

I am a fan obviously of Willis’ work and particularly of his latest idea. But I am left scratching my head and going back for a re-read about one or two points (I’m on my fourth reading as I write this).

The first is the “central” place he gives parallels between the first and sixth books (hereafter 1-6) in the Potter series as well as between Cuckoo and Ink Black Heart. Of all the parallels between books in each series and between the series, these may be the weakest. I see that book 6 is the ‘center’ of the tetractys, the holy Quartnion, and that one would expect to see echoes or links between the beginning and the center of the figure. I just don’t see the examples Willis uses for this relationship as especially vivid parallels. It’s the only place in his argument that I felt the pieces were being forced.

And it’s unnecessary. He mentions the much stronger connections between Philosopher’s Stone and Order of the Phoenix, first detailed by Joyce Odell ‘The Red Hen,’ and those between Cuckoo’s Calling and Troubled Blood; 1-5 seems a much stronger connection than 1-6 and is a better tetractys link as well (1 and 5 ‘touch’ while 1 and 6 do not).

I theorized in 2010 that the best geometric figure for understanding the Harry Potter books, because of the very strong echoing in books 1 and 5 as well as 3 and 7, was not a turtle-back ring but an asterisk (see Harry Potter for Nerds, 37-82, or Harry Potter as Ring Composition and Ring Cycle, 31-66). If Running Grave has strong echoes of Career of Evil in it per the Potter books’ relationship, I’ll have to wonder if that isn’t a blow to Tetractys Theory because I don’t see how the Quaternion links those numbers as the asterisk does.

My other quibble with Willis’ necessarily abbreviated presentation is that he is obliged to dismiss the Eros and Psyche mythic elements deployed in Troubled Blood’s office scene after the American Bar interview with Oakden and those in Ink Black Heart as foreshadowing or hints of the real division between Robin-Psyche and Strike-Cupid that will happen at the end of Running Grave and last the next two books. As noted above, though, we’ll find out in September in Running Grave whether those Eros and Psyche elements were just pointers or the actual substance of the template-connection. If Robin and Charlotte have their confrontation in Strike 7 and Ellacott is sent to hell on a mission by Venus, that, too, will be a blow to Tetractys Theory.

I call these objections “quibbles,” which is to say “trivial complaints,” because, next to Willis’ exposition of the structural meaning of Rowling’s work to date and into the future (!), they are relatively pathetic nit-picking in defensive face-saving for my having missed (or being unable to conceive, frankly) what he has seen and explained. His discussion of

the first four books as quaternal introduction,

the next three as a triad nigredo (which explains in passing curious elements of the series that break with the Hogwarts ring and alchemical sequencing that others, myself included, have noted and tried unsuccessfully to ‘make work’ within PSI and other critical frames), and

how Running Grave may complete this Tetractys level and introduce the dyad and monad pairs per Rowling’s mythological templates, on the models of her three stand-alone novels as albedo and rubedo, to complete her second Pythagorean cum Platonist pyramid of traditional symbolism,

is one of three things.

It is a Perennialist wish-fulfillment exercise, the most ambitious and magisterial overview of her writing attempted to date, one that unflinchingly incorporates all the ideas and tools previous critics have identified into a harmonious synthesis, or both. I look at my criticisms of Tetractys Theory above and see a street urchin throwing pebbles at the exterior walls of a gothic cathedral.

A more substantive objection to Willis’ achievement is, noting respectfully all he is brought together and explained, to note the elephant question in the room for anyone aware of Rowling’s postmodern political postures and public priorities independent of her charity efforts (I hesitate to dignify all of the above by calling them “beliefs”). “How does one square the ultra-traditional and uncompromisingly spiritual nature of the symbolism and structures in play, ideas typical of the pre- and anti-modern Greats, with her pedestrian and conventional views, the blind-spots characteristic of our time?”

That isn’t a new question, by the way. It’s been the head-scratcher of Rowling Readers since the Christian content and hermetic symbolism of her work was identified more than twenty years ago. Willis’ effort here, though, takes the dissonance between the mind of Rowling the Artist and of Rowling as Activist into cacophonic volume. One could, I suppose, reconcile the two by positing that the author’s stand against transgenderism and Gender theory in general rests more on her traditional views of the immortal soul and archetypes than her strident feminism, but that would mean ignoring her full-throated endorsement of lesbianism and pre-natal infanticide.

We all, of course, are incarnations of contradictory beliefs and practices. I think we are best served as serious readers of her work in leaving the sorting out of Rowling’s mélange of beliefs, for the most part, to her future critical biographers. I suspect that, if Willis is right, the efforts of said biographers will turn on reconciling or attempting to explain the seeming contradictions of the traditional and postmodern elements of her life and work.

Planning, Squared

In my several books about Harry Potter and especially after writing Spotlight, my discussion of the Quadrigal dimensions of Stephenie Meyers’ Twilight books, a remarkable segment of even these authors’ most ardent fans thought my interpretations were a ridiculous over-reach. I was, to this way of thinking, making the stuff up, seeing what I wanted to see but wasn’t there, and, in the end, giving these writers much more credit than the work warranted. I dismissed these dismissals then and now as little more than ignorance tinged with misogyny, again, especially with respect to Meyer qua ‘Mormon Housewife.’ Readers who respond to revelations of auctorial artistry they missed and could not imagine doing themselves as “impossible,” in my experience at least, are simply revealing their own blind-spots and prejudices.

I’m speaking this harshly because I am obliged to confess that I had similar thoughts about Evan Willis’ Grand Unified Theory of Everything Rowling Has Written. Could she possibly have planned these twin towers of tetractes, a set of twenty novels written in parallel with mirroring themes and meaning? “Is he nuts?” I wondered.

I happen to know he isn’t crazy; Willis is a remarkably sober young man. And the theory has legs to stand on. So, how could Rowling have planned this double tetractys of stories? Does even the timeline work?

We know from the intricate structure of the Hogwarts Saga and Rowling’s confession that her obsession is with planning that, despite The Presence’s telling Lev Grossman that she wrote those books “pain to brain,” i.e., akin to a ‘pantser,’ the seven novels were planned in great detail before Philosopher’s Stone was finished. I think it safe to assume that a ten-book structure of which the Potter novels were only the first two of four layers of meaning had not occurred to her then.

For the Tetractys Theory to work, she had to have at least conceived the three book cap of the first quaternion — Casual Vacancy, The Ickabog, and The Christmas Pig — when she was planning the ten book Strike series. As preposterous as that may seem, it is certainly possible.

Recall that there were five years between the publication of Deathly Hallows in 2007 and Casual Vacancy in 2012. If we assume, no great stretch, that she was planning the Strike novels in this interval in addition to writing Vacancy, then the twin tetractys becomes possible on a timeline. What makes this possibility hard to see is Rowling’s not having published The Ickabog until 2020 and The Christmas Pig until 2021, even though she has been relatively open about these books both having been planned many years previously, the first as a story for her children between 2003 and 2007 and Pig in 2012. Both were in hand for the most part during the critical period of her planning the ten novels of the Strike series.

There are reasonable objections to this, of course. Rowling’s story-telling in the media about pulling these stories out of a drawer just for Covid-lockdown families and for a Christmas story treat would have to be added to the ‘Rowling is a Manipulative Liar’ file. Frankly, it’s a pretty thick file, so I have no problem on this count. Why would Rowling reveal the tetractys structure of her first ten books or the Strike work in progress? There’s no benefit there to her or her readers (see her refusal to answer questions about PSI for another example of that).

The more likely objection, I’m afraid, is the one even I had, the one that simply reflects astonishment that the author would have taken her planning to this remarkable height, absolutely unprecedented if true in the history of English letters. I trust those much more versed than I am in this field to school me if I am wrong in that estimation.

Given what we know of Rowling’s planning in the Hogwarts Saga, though, and the parallels she has embedded in the Strike series with each book’s apposite Potter number, why should we doubt that she found another even higher gear for her story scaffolding and intra-textuality? Especially in light of Willis’ synthesis of the mythological, alchemical, and hermetic elements in her work that are the foundation of Tetractys theory, it has a certain wonderful likelihood, especially if one has put aside the remarkable conflict between traditional and postmodern thinking in her work and public life.

An Alternative Figure: The Celtic Cross

One of the strengths of Tetractys Theory is the absence of another credible explanation or series structure that answers the riddle of Rowling’s parallel series efforts and the declaration by author and publisher that the Strike series will be ten rather than seven books in length. My ad hoc effort to predict how this could work, namely, that Running Grave will parallel Deathly Hallows as the previous six mysteries have their Potter numbers and in that will be the de facto climax of the series, was in truth a confession that I did not see how it could work. “Seven plus Three Add-ons” said without saying out loud that the last three books, if the series was indeed ten books long, would be stand-apart mysteries not part of the real Strike septet (think Fantastic Beasts if the screenplays had been sequels rather than prequels). Willis’ theory is coherent, credible, and challenging, and, in those qualities, it has no rivals to date. To question it effectively, an alternative explanation for a ten book Strike series will be necessary.

Don’t look to me for that; I’ve taken my swings and missed on this subject.

I feel obliged to note, though, that it seems extremely unlikely to me that the tetractys pyramid will act as the Deathly Hallows symbol equivalent in Running Grave that the triangulated and bisected circle did in the seventh Potter novel. Given the I Ching epigraphs and the harmony of tetractys symbolism with traditional Chinese as well as Platonic and Christian cosmology, as Willis explained, maybe it will be. It seems a real stretch to me despite this connection because there is an alternative symbol, one we have already seen in the Strike books and suggested in the Rowling-twitter headers, that is a much better match with the Deathly Hallows pictogram.

That symbol is the Celtic Cross.

I discussed the esoteric meaning of this particular cross in my exegesis of the second card in Talbot’s True Book Celtic Cross tarot card spread:

The Celtic Cross spread is called what it is because the ‘Celtic’ form of the Christian two-bar cross features a circle around the nexus of the vertical and horizontal arms; the radiant point of the extensions is simultaneously the center of the circle, which puts its emphasis on the origin of both if visualized as a Cartesian coordinate graph. This Celtic form highlights the Logos nature of the Cross and the creative principle aspect of the second person of the Christian Trinity, God’s Word. The Celtic Cross tarot card spread’s first two cards are this “crossing point,” the next four cards encircle it, and the remaining four make up the staff or vertical arm of the cross, whose tenth position, the resolution card, if placed over the circle to complete the cross, coincides with the radiant point of the first two cards. The round towers of churches in Norfolk and elsewhere, in addition to their use as defensive citadels, have their shape in keeping with this symbolism of the circle cued to vertical extension, earth to heaven (whence its greater power as a fortification contra strictly horizontal, worldly forces).

The cross outside the Alymerton round tower church Rowling visited is a Celtic Cross.

How does the Celtic Cross compare with the Tetractys as a potential stand-in or parallel with the Deathly Hallows symbol in the seventh Potter novel?

I think it has three distinct advantages.

First, it is a symbol Rowling has used to great effect in Troubled Blood, albeit via the St John’s Cross rather than the Celtic Cross as such (these crosses, as the name ‘St John,’ the Logos theologian, suggests, both are icons of the Creative Word). The Celtic Cross tarot card spread, as I have argued, was an embedded key to the Margot Bamborough mystery and it is not much of a walk from this and Strike5’s extensive cruciform imagery to the idea that the Alymerton round tower church cross will be a big part of solving the Running Grave murder case.

Second, think about Deathly Hallows and the moment Hermione and Harry realize the triangular eye is more than a glyph in a children’s book. They are in a churchyard on Christmas Eve and see it on a Godric’s Hollow headstone. I think it easy to imagine a parallel moment in the Alymerton parish church grounds when Robin and Cormoran visit.

Third, there is the implicit sexual content of the Celtic Cross, one hard not to see in the tarot card spread. The circle around the first two cards is yonic and the staff obviously phallic; the two taken together, with the staff’s end point, the resolution card, laid over the inner cross, is an image of coitus. This repeats the imagery of the Deathly Hallows symbol, whose vertical line is phallic, the circle between two spread lines yonic, and their conjunction an image of sexual congress.

This symbolism, as in Rowling’s hilariously sexual imagery in the climactic scenes (!) of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (the giant Basilisk in the Chamber, a place only accessible through the lady’s room loo hole-in-the-wall, down a long slide, etc.), does not contradict its spiritual content; the Chamber of Secrets battle “miles beneath Hogwarts” is simultaneously a Freudian comedy and a Medieval Passion Play or Everyman re-telling. In Rowling’s psychomachia, especially in the Strike series with its Soul-Spirit Shakespearean allegory in play, sex is in addition to its passionate element something of a cipher for conjunctio oppositorum, the communion of self and transcendent Other.

I prefer, truth be told, the tetractys as a symbol of the ten book series because of Willis’ explanation of the four, three, two, and one levels of the image. Having said that, I find it a lot easier to imagine the deployment of the Celtic Cross, ten parts at least in the tarot card spread, in Running Grave, especially as this symbol is often used as a static grave marker or headstone.

So What?

Willis does not explore at length how the tetractys structure buttresses the core meaning of Rowling’s artistry. He notes almost as an aside:

And then The Christmas Pig, structured according to Dante (reflecting via knight-move our Tetractys center in Snape at 6), plays the role of the Monad. Here the autobiographical Lake-and-Shed central theme in Rowling’s work of Loss in relation to motherhood is dealt with directly as the central driving theme of all 10 books. 1-6-CP knight-moves through the center presents the Dantean narrative across our Tetractys, 4-6-CP presents the noble unexpected sacrifice (Cedric/Dumbledore/CP). This Christmas Pig Monad thus works as the core of what all other nine books sought to express.

This is perhaps the most exciting part of Willis’ argument to me and the most disappointing at the same time.

If he is right, Christmas Pig, the “monad” book of the first Tetractys Tower, acts as the “core” meaning of the first ten books series. As I have written about at great length, Pig with the possible exceptions of Troubled Blood and Deathly Hallows, is the best thing Rowling has written and the first thing I recommend to new readers of her book. It’s Perennialist symbolism and Dante-esque psychomachia jump off the page, Rowling’s depths at their most accessible, in a laugh-out loud Christmas-Become-Easter story. Tetractys Theory confirms the importance of Christmas Pig in Rowling’s oeuvre and suggests that the “monad” parallel in Strike10 will be similarly challenging and delightful. (See my ‘Perennialist Reading of Christmas Pig’ posts listed at this Pillar Page for much more on this).

That’s exciting; the disappointing part is that Willis said nothing about the psychomachian or soul’s allegorical journey to perfection aspect of Rowling’s work. I have argued that this is the golden thread that joins the author’s traditional symbolism, use of mythological templates, hermetic sequences and coloration, as well as her chiastic structures. Other than his aside about “Loss in relation to motherhood",” there isn’t any mention of or pointer to Rowling as writer of spiritual allegory. This may be because Willis does not agree with me on this point, that he didn’t have space in an already long piece to discuss it, both, or neither.

Time will tell, if the future holds more Willis exposition on this structure, especially post Running Grave, as I hope very much it will. Personally, I think Tetractys Theory, because of its explicitly traditional, which is to say ‘theocentric,’ cosmology, will serve as another buttress to the psychomachian allegory reading of Potter, Strike, and Rowling’s other work sans collaborators. But we’ll see!

I look forward to reading your thoughts on Tetractys Theory, especially if you have a moment to write today, before we are all distracted by the Running Grave cover release and teaser material tomorrow. Thank you to Evan Willis for sharing his Tetractys Theory here and, in advance, to you for sharing your reactions to his ideas and my first thoughts!

This is why Hogwarts Professor continues to be a great place to advance literary scholarship!! Wonderful pair of posts

I wondered whether your thoughts on Rowling's planning Strike in parallel with Potter would be affected if we acknowledged that she wrote Cuckoo before Vacancy, even though the latter was published before the former.