Reading 'Running Grave' as the End of the Strike Series (B)

Strike7's Parallels to 'Lethal White,' the Series Turn, that Make it the Completion of a Ring Cycle

Is The Running Grave the end of the Cormoran Strike series? Obviously not; the author and publisher have said there will be as many as three more books and there are a bundle of story-lines that need to be tied up.

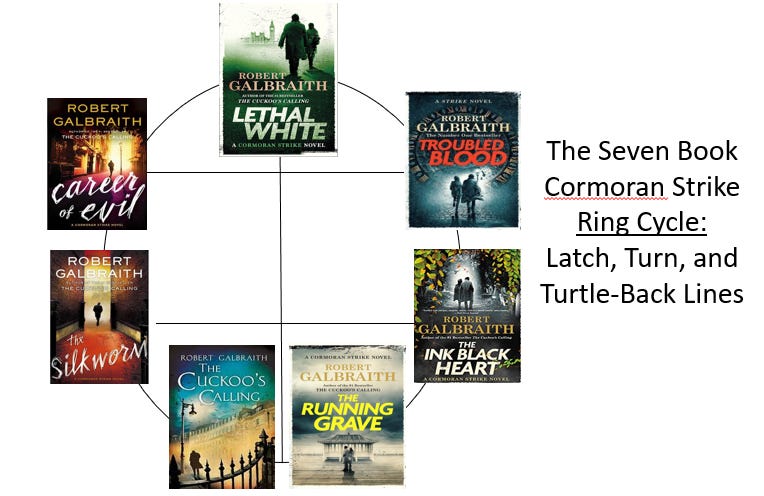

Having said that, though, there are significant reasons for thinking that the series as originally laid out was designed as a seven book ring cycle with the first and last books as a ‘latch,’ the fourth novel as the series ‘turn,’ and the books between the latch and the turn, before and after, are in parallel. It the sense of ‘structure’ or ‘design,’ the seven books we have at the publication of Running Grave is a complete set.

Let’s review the traditional story scaffolding Mary Douglas called “ring composition,” just in case all or any of those terms are still unfamiliar to you.

A proper ring composition has three essentials with one add-on nicety. The three ‘musts’ are the latch of beginning and end, a turning point that echoes the start and points to the finish, and so-called turtle-back lines that connect the story points going out from the first chapters to the turn and those chapters coming back to the latch closers. (The add-on nicety is rings-within-those-rings — and this series has rings within its rings within its rings, Rowling writing each book within the cycle-ring as a ring unto itself and with chapter sets inside those rings as autonomous rings, too.) Charting the series ring, the set of seven books as a cycle with latch, turn, and turtle-back echoing, cannot be finished until the last book is out because the seventh book is required both for establishing if there is a proper latch with the opening book and if the book that is the cycle’s turn foreshadows the last book in the series.

Now, as noted in my last post, before Running Grave came out we already had The Silkworm-Ink Black Heart and Career of Evil-Troubled Blood turtle-back lines established and we’d also demonstrated the really strong connection between the first book in the series, Cuckoo’s Calling, and the fourth book turn in Lethal White (again, see the three posts on that here, here, and here and the two posts here and here on the ‘Missing Page Mystery’ as well). What was left to do, if the series was a seven book ring cycle, to repeat myself, was test the Cuckoo’s Calling and Running Grave connection to see if they acted as the cycle’s latch and to review Lethal White to see if it foreshadowed Running Grave the way it had echoed Cuckoo’s Calling.

Having established in the first part of this three part post (to my satisfaction at least) that Strike1 and Strike7 are indeed a latch, all that’s left really is to write out a thorough Strike4-compared-to-Strike7 review to see if Lethal White is really the cycle’s turning point. Can we see pointers to the series finale, Running Grave, in the cycle’s turn, Lethal White?

The Series Ring’s Turning Point: Does Lethal White Foreshadow Running Grave?

I think it does. I have found and written up just over fifty correspondences between the central and the seventh Strike novel and sorted them into four categories: the Big Deals, the Character Parallels, the Clear Line Echoes and Plot Points, and the Grab Bag of everything else that made me wonder when re-reading Lethal White, “Does that sound like something in Running Grave?” It makes for a long read, obviously. The good news? The most important correspondences are first and the least, last.

The Big Deals: Correspondences You Cannot Un-See Once You’ve Seen Them

The Murder Mystery Plot

The surface story or plot drama of White and Grave are fun-house mirror reflections. See if you connect the dots between the plot summaries below:

In Strike4, Jasper Chiswell, a Minister of the Crown, learned about Strike because of the detective’s search for Billy, a mentally ill young man with an obsession about what he thinks was the murder of a child years ago. Papa Jasper hires the Strike Agency to get dirt on opponents (Billy’s hateful older brother specifically). Halfway through the novel, the investigation becomes a murder inquiry. Robin spends much of the novel undercover in dangerous circumstances at Westminster which causes great stress on her failing relationship with her husband.

In Strike7, Sir Colin Edensor, a knighted government official, hires Strike and Ellacott to help him free his son Will, a gifted but ‘on the spectrum’ young man whose idealism has made him easy prey for a religious cult. Sir Colin is not supported by Will’s hateful older brother in this decision. The investigation begins with efforts to get dirt on the Universal Humanitarian Church and Papa J but halfway through the epic mystery Strike is given permission to expand his investigation to include the long-ago murder of a child. Robin spends much of the novel undercover at the cult’s Norfolk property in dangerous circumstances which causes great stress on her still frail relationship with a new boyfriend.

The Foundation Crimes

Everything Rowling-Galbraith writes has a ‘foundation crime’ that is drawn directly from the Lake of her unconscious mind’s unresolved issues. In Harry Potter, it is the family romance of Merope Gaunt and the child conceived in a “coercive love.” In the Fantastic Beasts films it is the life and death of Ariana Dumbledore. [I’ll be posting on the subject of ‘foundation crimes’ at length in the near future in a full survey of Rowling’s 21 novels, screenplays, and stage play plot.] In each of the Cormoran Strike novels and the series as a whole there is a deep backdrop mystery that is the point of origin for the surface plot’s investigation. The foundation crimes of White and Grave are in parallel. Connect the dots between these thumbnail synopses:

In Strike4, Papa Jasper leaves his first wife, a woman of quality, for an affair with Ornella Seraphin, a self-confessed gold-digger working a pregnancy trap (424, 515). Freddie Chiswell, the older boy of the first marriage, in Billy Knight’s eyes at least, ‘murders the child of his father’s lover by strangling him in a ritualized scene at night as the leader of a group of adolescents. His motivation is the hateful bitterness of a an older child for his younger step-sibling in revenge for his father’s betrayal of the forgotten mother. Jasper is murdered in turn and in time by Raff, his illegitimate off-spring, and his second wife Kinvarra who is in an adulterous relationship with her step-son. [See below for the ‘true’ and ‘real’ foundation crime of White.]

In Strike7, Papa J’s wife dies and he takes up in short order with Mazu Graves, a married woman with a young daughter, Daiyu. Abigail Glover, the daughter of Papa J’s first marriage, in her role as the leader of a group of young adults has Daiyu, her despised step-sister, strangled and then butchered in a ritualized scene at night. Her motivation is the hateful bitterness of an older child for her younger step-sibling in revenge for her father’s neglect of her and his betrayal of the forgotten mother (whence the return to Comer beach). Papa J is destroyed in turn, along with his life’s work, the UHC, and his second wife, by the Agency’s exposure of this crime.

Mind-Control and Brainwashing

The surface story of Running Grave is all about the Universal Humanitarian Church, a cult that is an amalgam of the worst crimes and hypocrisies of the Roman Catholic Church (search for ‘Irish orphan sales’ and ‘pedophilia’), the Latter-Day Saints (see ‘polygamy in the name of religion’), Scientology (see Going Clear, the book or the documentary for the catalog of correspondences or just search ‘Sea Org’ for the analog of Chapman Farm), and Werner Erhard of EST and the Forum for the historical Jonathan Wace. From the gun, especially in the too few scenes with Strike’s step sister Prudence, the conversation and plot events are about cult mind control and their brainwashing techniques.

Lethal White is not so obviously about these subjects but it is the background theme, as Strike points out in the early going: “Getting to be a bit of a theme, that, isn’t it? People who’re supposed to be too crazy to know what they’ve seen” (179). The UHC is a religion that has charity as its public face which screens the reality of its underbelly from outsiders. Its Strike4 charity equivalent is the Wynn’s ‘Level Playing Field’ charity for handicapped athletes, which Geraint has turned into his personal treasure chest and means of access to young women.

The religion parallel is in the acronym organization in White, C.O.RE., ‘Community Olympic REsistance,’ and the Real Socialist Party, in both of which the faith-based brain-washing is superficially political but immersed in ‘Greater Good’ Marxism, the greatest criminal cult of the 20th century and today. The main line of indoctrination in both groups, as in the UHC’s depiction of ‘Bubble World,’ is to reveal to their potential members that they have been “brainwashed,” usually a revelation that is preface for a man getting into a woman’s pants (cf., pp 401, 438, and 444 for Rowling’s comic depiction of this).

The Truth and the Real

The Real Socialist Party, in its claim of being the real deal of Marxism, is the analog of the UHC, of which the core public teaching is about the “true reality:”

[Taio Wace proclaimed at the Rupert Court Theory that the audience’s beliefs were shaped and maintained by] ‘… a conspiracy so vast, it is literally unseeable, because we live within it, because it forms our sky and our earth, and so the only way – the only way – to escape, is to step, quite literally, into a different reality, the true reality.’ (161, emphasis in original)

Both books feature principals and ancillary characters who are consumed by questions of reality and truth. Billy Knight in Lethal White cannot escape the memory of the Uffington White Horse murder and his question; “I’ve got to know if it’s real” (500). He asks this question about his memory and his surroundings; “Is this real?” is almost his mantra (512, cf., 597, 604, 643). Robin, after her face to face life-and-death confrontation with Raff and his pistol on the barge at the end of White, notes that “Nothing seemed real” and “she realized that Strike was standing beside her, and he seemed the only person with any reality” (633).

The great mind-screw of the UHC on its believers is that the Drowned Prophet boogey is real. Two cultists in recovery, Will Edensor and Flora Brewster, meet outside Chapman Farm and their principal discussion is about the reality of this avenging phantom:

‘But I’ve never seen her again, since New Zealand,’ said Flora. ‘Except, like I say, sometimes if I drink I think I can hear her again… but I know she’s not real.’

‘If you really thought she wasn’t real, you’d have been to the police.’… ‘I know she’s real, and she’s going to come for me,’ Will continued, with a kind of desperate bravado, ‘but I’m still going to turn myself in. So either you do believe in her, and you’re scared, or you don’t want the church exposed.’

‘I do want them exposed,’ said Flora vehemently. ‘That’s why I spoke to the journalist and why I said I’d meet you. You don’t understand,’ she said, starting to sob. ‘I feel guilty all the time. I know I’m a coward, but I’m afraid—’

‘Of the Drowned Prophet,’ said Will triumphantly. ‘There you are. You know she’s real.’

‘There are more things to be frightened of than the Drowned Prophet!’ said Flora shrilly. (832)

After Robin shares how the Drowned Prophet illusion was created in the Temple and classrooms, Flora is freed from this consuming delusion — and displays it to Will by speaking freely about the ‘real’ ‘Divine Secrets:’

‘The Drowned Prophet isn’t real,’ Flora told Will. ‘She’s not.’

‘If you honestly believed that,’ said Will, with a trace of his former anger, ‘if you genuinely believed it, you’d reveal the Divine Secrets.’

‘You mean, the Dragon Meadow? The Living Sacrifice? The Loving Cure?’

Will glanced nervously towards the window, as though he expected the eyeless Daiyu to be floating there.

‘If I speak about them now, and I don’t die, will you believe she’s not real?’ said Flora.

Flora had shaken the hair out of her face now. She was revealed as a beautiful woman. Will didn’t answer her question. He looked frightened.

‘The Dragon Meadow is the place they bury all the bodies,’ said Flora in a clear voice. ‘It’s that field the horses are always ploughing.’

Will emitted a little gasp of shock, but Flora kept talking. (838)

Strike, too, in his critical reflections in the Aylmerton Chapel after learning of Charlotte’s death, thinks about their fundamental disconnect, namely, “reality:”

Six years since the relationship had ended for good, Strike had come to see that the unfixable problem between them was that he and Charlotte could never agree what reality was. She disputed everything: times, dates and events, who’d said what, how rows started, whether they were together or had broken up when he’d had other relationships. He still didn’t know whether the miscarriage she claimed she’d had shortly before they parted forever had been real: she’d never shown him proof of pregnancy, and the shifting dates might have suggested either that she wasn’t sure who the father was, or that the whole thing was imaginary. Sitting here today, he asked himself how he, whose entire professional life was an endless quest for truth, could have endured it all for so long. (424)

Ah, the truth! Robin Lethal White’s mad final break with Matt Cunliffe comes to a head when she finally confronts him with “I’m telling you the truth, this the whole truth” about her vocation as a detective and the lies of their relationship. She has the courage, as she spits into his denials and dismissal of what she learned in therapy as self-justifying “bullshit” that it was in her counselling that “I learned to tell the truth!” (487-488). The real foundation crime murder in White, unlike the strangulation death Billy thinks he saw, was Freddie’s treatment of teenaged Rhiannon Winn that led to her suicide; Raff learned about it from the younger sister of a witness to that crime, a woman named ‘Verity,’ which derives from veritas, the Latin for ‘truth.’

In Running Grave, Robin as Rowena testifies to a distraught Emily Pirbright in a Norfolk toy shop about the truth:

‘Sometimes,’ said Emily, ‘I want to scream the truth, but… that’s egomotivity…’

‘It isn’t egomotivity to tell the truth,’ said Robin.

‘You shouldn’t talk like that,’ said Emily, on a hiccup. ‘That’s how I got relocated.’

‘I joined the church to find truth,’ said Robin. ‘If it’s just another place where you can’t tell it, I don’t want to stay.’

‘“A single event, a thousand different recollections. Only the Blessed Divinity knows the truth,”’ said Emily, quoting from The Answer.

‘But there is truth,’ said Robin firmly. ‘It’s not all opinions or memories. There is truth.’ (508)

Struck by this thought, Emily shares her hidden truth with Robin, that the Drowned Prophet hadn’t drowned, the truth that eventually brings down the UHC.

With the help of Patricio Tarantino, I am doing a deep dive on Rowling-Galbraith’s use of the “real” in her Cormoran Strike novels (for her use of it in her other books as well as Running Grave, see the discussion in the conclusions of this post explaining Carrie Woods’ several comments about the ‘real’ in that character’s ch 97 conversation with Strike). In anticipation of that study, though, the line connecting Grave and White is at least in part about what is real and the surety that there is truth.

The Mythic-Religious Backdrop

White Horses are everywhere in Lethal White; from the sick white foal of the Stubbs painting from disease the book takes its title and multiple pub signs and names to the white horse death omens of Ibsen’s Rosmersholm, the characters even become unnerved by the equine ubiquity. The biggest representation of all, though, is the Uffington White Horse, the eye of which prehistoric hill figure is the location of Freddie Chiswell strangling the child Raff. Freddie compounds his desecration of the monument by killing a pygmy horse with a rifle from a sniper position on

the manor rooftop. The White Horse, it seems, took its revenge via Leftenant Chiswell’s death by sniper fire in Iraq. Raff, too, may have begun his journey to murdering his father in a wish he made as he expired in the eye of the mythical horse in Uffington.

The mythic-religious backdrop of Running Grave is concealed in plain sight beneath the fraudulent farce of faith that is Jonathan Wace’s UHC. The true believers not born within it are all drawn into his cult by his persuasive, signature invitation that they “admit the possibility” of a greater reality than the rat race of material concerns. Tossing about authentic revelations from Orthodox religious traditions, Papa J touches on inquirers’ desire for and capacity to grasp a transcendent truth beyond their individual “egomotivity.” That he is a false prophet, however, does not demonstrate that there are no true prophets, just as his false and human-made syncretism of a religion that serves as his vehicle for personal power and wealth does not prove that the faiths and scriptures that he misrepresents are frauds and cults. If anything, the existence of the fictional UHC points to the depth and strength of human longing for and means of knowing what is true and real beyond the ephemera of our transient lives.

White and Grave are conjoined as the most in-your-face depictions of the mythic and religious in their surface stories.

The Abuse of Women and Children

The abuse of women, especially sexual abuse, is not restricted to White and Grave, certainly; I’ll say more about that in the review of Career of Evil’s links to Strike7. In the conjunction of child abuse and the abuse of women, though, the fourth and seventh books stand out.

Lethal White begins with Billy Knight’s cry for help in finding out who killed the child he saw murdered in the eye of the White Horse when he was a very young boy himself. The reader is told that Billy grew up inside a nightmare:

“Poor little Billy,” said Izzy vaguely. “He wasn’t right. Well, you wouldn’t be, would you, if you were brought up by Jack o’Kent? Papa was out with the dogs one night years ago,” she told Strike and Robin, “and he saw Jack kicking Billy, literally kicking him, all around their garden. The boy was naked. When he saw Papa, Jack o’Kent stopped, of course.”

The idea that this incident should have been reported to either police or social work seemed not to have occurred to Izzy, or indeed her father. It was as though Jack o’Kent and his son were wild creatures in the wood, behaving, regrettably, as such animals naturally behaved. (350-351)

Strike and Robin spend a good part of the novel looking for ‘Suki Lewis,’ a young girl they think might have been the strangled child Billy remembers. “Suki had vanished from her residential care home in Swindon in 1992” Strike learns, but it is only in talking at last with Billy in a psychiatric hospital and Tegan Butcher at the racetrack that he finds out her story had a fairy tale ending; Suki’s real name was Susanna McNeil and she’d escaped from a crazy care mother and found her real family in Aberdeen, where she was thriving (cf. 500).

In Running Grave, it is the children of Chapman Farm that are living an almost cage-child existence apart from their parents, which is to not mention the children being trafficked out of Manchester and the tortured life of Jacob Pirbright-Wace. Jacob’s mother, Louise, suffers through her second son’s living death hidden from the world in a Chapman Farm attic. More on this in a moment.

Women do little better than their progeny with respect to abuse. In White, Robin has her husband Matt all but sexually assault her after the ball when she returns home in the Green Dress. Geraint Winn’s angry phone call when she and Strike are driving to Uffington, laced at that screaming match is with his sexual invective, induces her panic attack which forces the best of drivers to have to pull onto the verge.

Her exchanges with Winn at Winchester in his MP office are echoed in Robin’s private meeting with Jonathan Wace, during which he touches her breasts and reaches for her pudenda. The threat of Taio Wace’s “increasing” her throughout her time undercover at Chapman Farm and specifically after her release from the Box and time with Jacob Pirbright, is what induces her controlled panic attack escape to Strike.

The Suffering Mother of a Dead Child

I mentioned Louise Pirbright and the agony of her living son’s life at Chapman Farm. That introduces the parallel stories of suffering mothers and the painful memories of their dead children in White and Grave.

Strike4 is named for an equine disease in which a foal is born doomed to an early death which its mother is unable to prevent. Kinvara Chiswell has lost a child by still-birth, which experience seems to have made her come unhinged (cf. 171, 355). In addition to the long-suffering Louise Pirbright in Running Grave, who loses all of her four children to the UHC in various ways, to include two deaths, there is Flora Brewster, whom the reader learns only very late in the store is unhinged as she is by her time at Chapman Farm — and the death of her baby there:

‘I had a baby there and she died. She was born dead. The cord was wrapped around her neck.’

‘Oh God,’ said Robin, unable to contain herself. She was back in the dormitory, blood everywhere, helping to deliver Wan’s breech baby.

‘They punished me for it,’ said Flora with a little sob. ‘They said it was my fault. They said I killed the baby, by being bad. I couldn’t tell Dad and my stepmum things like that. I never told anyone about the baby at all, until I started seeing Prudence. For a long time, I didn’t know if I’d really had a baby or not… but later… much later… I went to a doctor for an examination. And I said to her, “Have I given birth?” And she thought it was a very weird question, obviously, but she said yes. She could tell. By feeling.’ (831)

She eventually slits her wrists in a bathroom, is saved by her father, diagnosed as psychotic, and brought back to something like rationality via medication.

These seven correspondences between Lethal White and Running Grave, I think, are the ones to remember, especially the first two: the parallel story-lines and foundation crimes. The great majority of the rest are less structural or thematic than they are almost audible echoes or mirrored images between the fourth and seventh books, ties which hang like ornaments on the tree of these seven large-links. Having covered the big connections at some length, the character parallels, line and plot point echoes, and the stretches will be relatively cursory.

The Character Parallels: Pairs in Reflection and Same Character Echoes

Billy Knight/Will Edensor

The troubled young men of the two books are reverse echoes of one another. They share a name, they both are the inciting incidents of the story-lines, they have older brothers who despise them and regret their relation, and they both wind up as featured players in the epilogues. They are opposites or contraries with respect to their backgrounds, one rich, one poor, their fathers, one caring, the other an alcoholic abuser of his younger son, and their educations. Will is a high functioning autistic man while Billy is suffering from schizoid affective disorder that makes his connection to reality problematic. As discussed above, though, Will, too, struggles with his grasp of what is real and what is not.

For more specific links, when Strike interviews Billy in the mental hospital, je is wearing a tracksuit (491-495). He gives his story as well as he can given his tentative grasp on reality but balks at talking about the crime about which Strike presses him (the gallows). His doctor caretakers are present and lead him away when his incomplete testimony is done.

When Strike speaks with Will after his escape from Chapman Farm, he, too, is in a tracksuit. He has a weak hold on reality, as well, and refuses to tell all despite Strike’s questions; he decides to hold his information about the real crimes he knows about until he is arrested. Pat Chauncey, his eventual caretaker, assumes control of the young man and his daughter at the close of the interview.

My favorite fun link between the two, though, besides the tracksuits, is that Billy thought escaping from the Winn bathroom would mean certain death (“thought the door had explosives around it” 501) and Will’s conviction that it would be “suicide” to leave the UHC property (142).

Della Winn/Mazu Graves Wace

The blind Minister of Sport and the mother of everyone in the UHC on the surface have little in common, but at the core they are sisters. Each is the mother of a daughter who died in tragic circumstances. Each is married to a cad with pronounced adulterous predilections who deceives his wife about the key aspect of their relationship; the men are reverse echoes of each other in appearance and manner as are their wives. Both have idealized paintings of their late daughters prominently displayed in their public spaces.

In Strike’s interview with Della in White he sees in her “the burning, frustrated maternal drive tinged with unassuageable regret” (478). Winn herself testifies to this in noting bitterly that the world thinks little of her in the end because the “proper role of a woman is carer” and “there is nothing lower than a bad mother” (479). Robin all but throws these lines in Mama Mazu’s face in their to the death confrontation in the Rupert Court Temple finale:

‘Daiyu never went to the sea,’ said Robin, advancing inch by inch. ‘Never went to the beach. It was all bullshit. The reason her body never washed up is because it was never there.’

‘You are filth,’ breathed Mazu.‘

Should’ve kept a closer eye on her, shouldn’t you?’ said Robin quietly. ‘And I think you know that, deep down. You know you were a lousy mother to her.’

Mazu’s face was so pale, it was impossible to know whether she’d lost colour, but the crooked eyes had narrowed as her thin chest rose and fell.

‘I suppose that’s why you wanted a real Chinese baby girl of your own, isn’t it? To see whether you can do any better on a second att—?’ (907)

What the Minister said of Kinvara, in great contrast with her situation, is a description of Mama Mazu as well: “Women like Kinvara Chiswell, whose entire self-worth is predicated on the status and success of marriage, are naturally shattered when everything goes wrong” (472). Both in the end are a little mad, a madness springing from grief for their daughters who died too young and for their failed marriages.

‘Dodgy Doc’/Dr. Adam Zhou

Dodgy Doc is Strike’s nickname for the plastic surgeon in Lethal White who takes advantage of young woman who want “breast augmentations” and the like but cannot pay with money. He does the surgery in exchange for “exclusive arrangements” in which they can repay him with their sexual favors. His business partner hires the Agency to gather evidence of this so he can dismiss the man from his upscale offices on Harley Street.

Dr. Adam Zhou is the New Age medical practitioner in Running Grave, who, though with premises even more grand than the cosmetic surgery where Dodgy works, is the reason the UHC has been able to disguise its abuses from the public eye as long as it has. He is much more dodgy and dangerous than his Lethal White reflection. Both are arrested in the end.

‘Papa’ Jasper (Chiswell)/’Papa J’ Jonathan Wace

The ‘Bad Dads’ of each book with the resonant names…

Charlotte Campbell Ross

Charlotte Campbell appears for the first time in the flesh after her near collision with Robin at the opening of Cuckoo’s Calling in the center of Lethal White where she accidentally meets with her ex-lover at the Paralympics Ball. Strike learns of her death at the page-count center of Running Grave and has an other-worldly conversation with her in the Aylmerton church.

In both White and Grave, Melady Bezerko manipulates Strike into a meeting at a restaurant by feigning a coincidental crossing of their paths. In Strike4, she runs in to him at Drummond Galleries and plays the difficult pregnancy card to get him him to walk her to and sit down at Franco’s, an upscale eatery where she says she is meeting her sister Amelia. In Strike7 she pulls the same trick by happening into The Grenadier during Strike’s interview with a gay friend of hers. In both cases she admits in the end to lying about her not having known he would be where she ran into him and her motives for being there. Amelia is not to be her guest after all; Strike meets Amelia at an upscale restaurant, though, in the Epilogue of Running Grave to close that circle.

In Strike’s conversation with Charlotte in both dining rooms he is brutal in his frankness that their relationship is over. In White he tells her point blank “Sixteen years, on and off, I gave you the best I had to give, and it was never enough,” he said. “There comes a point where you stop trying to save the person who’s determined to drag you down with them” (435). He goes so far as denying that she took care of him when he lost his leg because of her love for him; he attributes it to her love of “drama.”

“I acted like a spoiled bitch,” she said, “I know I did, then I married Jago and I got all those things I thought I deserved and I want to fucking die.”

“It goes beyond holidays and jewelry, Charlotte. You wanted to break me.”

Her expression became rigid, as it so often had before the worst outbursts, the truly horrifying scenes.

“You wanted to stop me wanting anything that wasn’t you. That’d be the proof I loved you, if I gave up the army, the agency, Dave Polworth, every-bloody-thing that made me who I am.”

“I never, ever wanted to break you, that’s a terrible thing to—”

“You wanted to smash me up because that’s what you do. You have to break it, because if you don’t, it might fade away. You’ve got to be in control. If you kill it, you don’t have to watch it die.” (434-435)

I confess I’d forgotten this Franco’s frankness by the time I read Strike’s equally direct and unflinching critique of Charlotte’s motives for helping him at the time of his greatest need (Grave, 157-160). It must have been because he clearly hadn’t meant the “There comes a point where you stop trying to save the person who’s determined to drag you down with them” bit in Troubled Blood when he does save her from committing suicide. But he re-doubles the ‘cruel to be kind’ truth telling in Strike7, blowing up their shared “mythology,” transgressing a “sacred taboo,” and undermining the “foundation of her certainty that” he continued to love her. He means it this time and, in Part Four of Grave, ignores her cries for help quite coolly.

Nick Jeffery is posting tomorrow about the mystery of Charlotte’s suicide so I will leave my notes about the twined aspects of Charlotte in Strikes 4 and 7 with this note. In White, she is heavily pregnant and is struggling to walk as she departs from the gallery. The reader is told in the Epilogues that, indeed, she was really in a bad way; she had been hospitalized to save the twins she was carrying (638). In Grave, she tells Strike that she has breast cancer and repeats the claim in a phone message (158-159, 421). Strike doesn’t believe her and takes the self-justifying position in his Epilogue meeting with Amelia that her silence about cancer meant her sister didn’t have it: “Strike didn’t ask whether Charlotte had genuinely had breast cancer, though he suspected, from the absence of any mention of it from Amelia, that she hadn’t. What did it matter, now?” (936).

What if, as with her Lethal White struggles with pregnancy, the breast cancer diagnosis was real? Be sure to read Nick Jeffery’s post tomorrow.

Lucy Nancarrow X

Strike’s meetings with his sister Lucy Whose-Married-Surname-Will-Not-Be-Given in almost every book are not happy occasions. Except perhaps for an occasional commiserating moment during the death of Aunt Joan in Troubled Blood, Cormoran’s half-sister is a nag. The two exceptions to this rule are in Lethal White and, you guessed it, Running Grave.

In Strike4, Strike visits her home in the aftermath of nephew Jack’s near death experience from appendicitis. There are no attacks or persistent probing questions about his relationship status, he is good with his three nephews, and, outside of a little friction with brother-in-law Greg, all is sunshine and roses. He receives a call from a relation of a suicide immediately after (300-303).

In Strike7, Strike makes a point of meeting with Lucy after he takes the UHC case because the Norfolk commune where they spent the worst time of their childhood is in play. He learns from her that she was sexually molested there by the resident Dodgy Doc and that Mazu was the person who delivered her to the predator. Strike is taken aback at this revelation but has the most honest exchange with Lucy about their mother and shared childhood ever. The rest of his stay is positive, again, outside of Greg being churlish, with a fun time with his nephews an added plus (96-104). Strike recalls a meeting with Lucy at the end of the case in which she thanks him for what he had said to her at the case’s beginning and swears she will stop nagging him about his life choices (932). The next chapter he sits down with Amelia Crichton, the only full sister of Charlotte Campbell, to discuss her suicide.

Mitch Patterson

Strike’s only real competition in London, it seems, Mitch Patterson, detective, appears in Lethal White (238-240, 533) and is on his way to jail at the end of Running Grave (729).

The Line Echoes and Plot Point Parallels

“I love you, too”

Oh, boy, this line is a killer in both White and Grave. In White, Robin says it to Matt on their anniversary and for the first time “:knew she was lying” (205). Strike is unable to tell the lie to Lorelei which begins the swift descent of their relationship (208). Robin screams at Matt in their final battle at the doorstep that “I don’t love you anymore!” (486). Points for honesty at last.

In Grave, after her escape from Chapman Farm Robin tells her boyfriend Ryan that she loves him in a post coital rote response but immediately wonders, “Had she just lied, or was she overthinking?” (673). Not much later, she laments what she’d said:

Those fatal four words, ‘I love you, too’, had brought about a shift in Murphy. It would be going too far to call his new attitude possessiveness, but there was a certain assurance that had been lacking before. (822)

Strike in addition to his blistering comments to Charlotte in The Grenadier tells her over the phone that they were “never fucking friends,” because “Friends don’t do to eachj other what we did.” She responds, “You’re with Robin aren’t you?” (369). Strike’s nuanced profession of love for Robin at the novel’s close is through this perception of Charlotte’s knowing “I was in love with you” (944), effectively exploding Robin’s world.

“How did you I was here?” “I knew you were there”

My favorite line by far in Running Grave is Robin’s telling Strike twice as she falls asleep next to him after her escape, “I knew you were there” (636). Their anterotic love, the friendship of selfless sacrifice and shared identity is all in that line, one reinforced by their shared bed sans sex.

At the end of Lethal White, we got a foreshadowing of this after Strike rescues Robin from Raff’s borrowed barge. “How did you know I was here?” she asks him (634). He didn’t know that she was there; he had to call around to get the location. But the idea is there — they know or find out where the other is. As Strike told Charlotte, “Friends have each other’s back. They want each other to be OK” (369).

“Rough childhoods don’t make a person a murderer”

Another clear echo: in White, Strike tells Izzie, “Plenty of people go through through worse than having a party girl for a mother and they don’t end up committing murder” (640). In Grave, it’s “A lot of people have dreadful childhoods and don’t take to strangling young children” (932). Both comments come in the books’ respective epilogue chapters.

“Lies People Tell Themselves”

In Lethal White, Strike observes about Kinvarra at New Scotland Yard, “Amazing, the lies people can tell themselves when they’re drifting along in the wake of a stronger personality” (604). At the end of Running Grave, he says the same thing about his relationship with Charlotte and Robin reciprocates about her blindness to Matt’s character, the lies they told themselves (943).

The Black Eyes of Rage

Matt’s eyes “turn black as his pupils dilated in shock” after being told by Robin that she doesn’t love him anymore (White, 486). Abigail Glover’s “eyes were jet black” when Strike asked her rhetorical questions about what Daiyu did the night of her murder (917). Daiyu’s eyes in the iconography of the Rupert Court Temple are described as “malevolent black eyes” (162, 894), her mother’s as “crooked near-black eyes” (401), and her step-father’s as “black and blank” in Strike’s backstage meeting with him:

Wace’s charm and ease of manner, his smile, his warmth, had vanished. Once before, Strike had faced a killer whose eyes, under the stress and excitement of hearing their crimes described, had become as black and blank as those of a shark, and now he saw the phenomenon again: Wace’s eyes might have turned into empty boreholes. (806)

That killer was Elizabeth Tassel in the climactic confrontation of The Silkworm: “The intensity and emptiness of her gaze were remarkable. She had the dead, blank eyes of a shark” (439) Blank, not black; that correspondence is reserved for the bad husband in Lethal White confronted with his failings, as Strike does Papa J in Grave.

The Third Eye

Raff presses a pistol barrel into Robin’s forehead in Lethal White, a move that gives her a “ring of white fire for a third eye” (619). Papa J’s talk at the Temple in Running Grave includes this observation about Shiva: his “third eye gives him insight but it may also destroy” (86).

Robin PTSD with Strike as Therapist

Robin has a panic attack in the Land Rover after a shouting match with Geraint Winn. She is comforted by Strike with an arm over her shoulders and frank conversation on the roadside verge. The police arrive, interview the pair, exeunt omnes. Strike buys Robin champagne at the racetrack to congratulate her on her divorce (White, 534-544).

After being pulled over the fence of Chapman Farm by Strike and their driving away, Robin has a meltdown in the BMW. She shares a prolonged hug with him in the car at the roadway inn parking lot and is comforted by their conversations in the hotel room. He buys her brandy for her nerves and to celebrate her release from the cult. The police arrive, interview them, and exit (Grave, 626-632).

The Class Tensions of the Endings

In the Epilogue of Lethal White, Izzy Chiswell meets with Robin, Cormoran, and Billy Knight to discuss the case and how it played out. Billy learns what really happened in the eye of the White Horse decades previously. Working class Billy is patronized by upper class Izzy for more reasons than his mental illness; she is clearly uncomfortable in a way that middle class Strike and Ellacott are not by dining with him.

In the first chapter of the Running Grave Epilogue, Cormoran and Robin meet with Sir Colin Edensor on his estate grounds. Sir Colin is from a working class family but has risen by dint of marrying well and his government service to the upper class. He has nothing but admiration and gratitude for Pat and Dennis Chauncey, the working class (lower middle class?) family that have been so helpful with his son and grand-daughter after their escape from the UHC in Norfolk. They in turn are frank and friendly with him, a man now well above their station, in discussing what is best for Lin’s future.

The Found Photos

One of the plot point absurdities of Running Grave is Robin’s finding old polaroid photographs in a Chapman Farm dumping ground biscuit tin, a bizarro implausibility discussed at some length in my exegesis of Part Three’s structure. The pictures are of naked people wearing pig masks in “various sexual combinations” and behaviors, all compromising (342-345).

The Lethal White near equivalent is Robin’s discovering in the Chiswell Manor bathroom (!) a stack of framed photographs on the floor, in which the astute detective finds a picture that is helpful in moving the case forward. If that link doesn’t seem very clear, Raff makes it definitive in saying to Robin as she exits the bathroom that he preferred ‘Venetia’ to ‘Robin’ because the name “made me think of masked orgies” (364-365).

Robin and the Lunatic with a Gun

At the end of White, Robin is held at gunpoint by psychopath Raff on his friend’s barge. It turns out the pistol isn’t loaded. In the action finish of Grave, Robin confronts Mama Mazu upstairs at the Temple and the madwoman pulls out a rifle. It’s locked and loaded as Robin discovers when taking the weapon from her.

Robin and the Walk Upstairs Alone

In Lethal White, Robin is left alone at the Chiswell Manor house as Strike and Kirvana check out the stables for intruders with her gun in hand. Robin is told not to explore the house, but, hearing a noise upstairs, investigates. Strike is not pleased by this risk-taking but she finds the Stubbs painting upstairs (586).

Robin again goes upstairs though instructed not to by Strike because she hears a sound needing investigation there. She, too, finds a crazy woman with mommy issues and a gun she shouldn’t have. Midge lets her know Strike is not happy she entered the Temple alone, but her success in subduing both Mazu and Becca Pirbright and saving the baby makes it hard to argue with her decision (905-909).

Big Hugs

The hug that haunted Strike and Robin ever after takes place during her wedding reception in Lethal White (25). They share a kiss, too, in Strike4, albeit inadvertently and on the lips as she leaves him at Jack’s hospital bedside vigil (235).

Strike hugs Robin to console her after her escape from Chapman Farm, as noted, and the embrace includes a Platonic kiss:

As Strike turned off the engine, Robin undid her seat belt, half rose from her seat, threw her arms around him, buried her face in his shoulder and burst into tears.

‘Thank you.’

‘’S all right,’ said Strike, putting his arms around her and speaking into her hair. ‘My job, innit… you’re out,’ he added quietly, ‘you’re OK now…’

‘I know,’ sobbed Robin. ‘Sorry… sorry…’

Both were in very inconvenient positions in which to hug, especially as Strike still had his seat belt on, but neither let go for several long minutes. Strike gently rubbed Robin’s back, and she held him in a tight grip, occasionally apologising while his shirt collar grew wet. Instead of recoiling when he pressed his lips to the top of her head, she tightened her hold on him.

‘It’s all right,’ he kept saying. ‘It’s OK.’ (627)

Hidden Murder in the Forest

The Agency investigates Billy Knight’s claim to have seen the murdered child buried in the dell below his father’s house. They travel to the Chiswell property, trespass through the forest, dig up the dell, and find the buried bones of a murdered miniature pony (White, 574-580). The crime of the older brother!

The murder in the forest of Chapman Farm — the crime of the older sister! — is confirmed when Midge travels to Norfolk, trespasses onto the UHC property’s forest, and finds the axe in the hollow ash tree (872)

“I’m So Bloody Stupid”

Robin bemoans her naivete on finding Sarah’s earring in Lethal White: ”I’m so bloody stupid” (465, cf. 489 “I should have walked out of the wedding” ). In the Epilogue of Running Grave, she repeats this observation as her lament to Strike that she “regretted within an hour [his] putting the ring on my finger” (943).

Landed Gentry in Decline

Remember the Gaunt family in Half-Blood Prince? Did you know that the name as well as the Dark Mark come from Vanity Fair, a William Thackerey novel? Check out this post from 2008 about Susan and Jerry Bowyer’s brilliant find. The link is important because both Gaunt families are gentry historically that have degenerated into poverty and vice.

I thought of them when reading Running Grave when Strike visited the Graves family manor in Norfolk and spoke with the Colonel, his wife, and the Delaunays, his daughter and her husband, the retired Marine. Their estate is in better order than the Chiswell property in Lethal White but each gives out the same vibe of grand families in decline, financial and in character.

Torture!

The gallows are described as “torture equipment” in Lethal White (562) and the box Robin inhabits in Running Grave as a “torture technique” (635, 646).

Dragons!

Billy Knight tells Strike the White Horse of Uffington looks much more like a dragon to him and it is on “Dragon Hill” after all (White, 496). Will and Flora talk about the UHC’s ‘Divine Secrets’ in Running Grave, one of which is the “Dragon Meadow” (838).

Which thinnest of echoes should act as a transition to the toss-up possibilities of parallels between Strikes 4 and 7.

The Stretches: Lighter Links Between Lethal White and Running Grave

Blue Hair

Robin wears “black and blue hair chalk” in Lethal White while undercover at the witchery shop (385) and dyes her hair blue to become Rowena in Running Grave.

Godchildren

Strike and Robin are godparents to Ilsa Herbert’s baby boy in the Running Grave opening as they should be to Qing/Sallie at its close. Lethal White has Robin playing the part of god-daughter to Jasper Chiswell while undercover as Venetia Hall and Drummond was godfather to both Francesca and Freddie.

Broken Conversation Clues

Robin overhears Flick talking with Jimmy Knight in Lethal White and must do what she can to fill in the blanks of what he is saying to understand the meaning. Running Grave’s equivalent is Strike’s wrestling with the recording of the Kevin Pirbright interview at a noisy bar, a broken conversation that yields the essential clue to his killer.

Bougie!

Jay Z is singing about a “bougie girl” in Lethal White (444) Robin refers to Bijou Watkins as “Bougie” the night she escapes from Chapman Farm (633).

French Hotel Names

Robin and Matt get the cheap suite at the luxury inn and resort La Manor Aux Quat Saisons in Lethal White, a turning point in their relationship (see ‘I Love You’ above) and in the case because of Raff’s meeting with Kinvara there. Strike stays at the Hotel de Paris in Cromer, where he learns about Cherrie Gittens on the beach with Daiyu and about Charlotte’s suicide. For the 1-4-7 Hotels with French names trifecta link, recall the Malmaison Hotel in Cuckoo’s Calling where the barrister sleeps with his partner’s wife.

The Three Ambition Check List

Strike has his three ambitions check list in Lethal White (417) as does Robin in Running Grave as she prepares to leave Chapman Farm (519). She manages to have the talk with Emily and one with Will but fails to retrieve the Axe.

Strike: Need for a Change

When Strike and Lorelei break up in Lethal White, she calls him out on his gross behaviors — and he seems to get it, that he needs to change his ways, if he’s not going to share that resolution with anyone (418-419). In Running Grave, he realizes the need for a a change in life direction, specifically about Robin but women in general, after his encounters with Bijou Watkins but most pointedly at the death of Charlotte Campbell-Ross:

And as he sat in this humble old church, with the round tower that lost its sinister aspect when seen up close, he looked back on the teenager who’d left Leda and her dangerous naivety only to fall for Charlotte, and her equally dangerous sophistication, and knew definitively, for the first time, that he was no longer the person who’d craved either of them. He forgave the teenager who’d pursued a destructive force because he thought he could tame it, and thereby right the universe, and make all comprehensible and safe. He wasn’t so different from Lucy, after all. They’d both set out to refashion their worlds, they’d just done it in very different ways. If he was lucky, he had half his life to live again, and it was time to give up things far more harmful than smoking and chips, time to admit to himself he should seek something new, as opposed to what was damaging but familiar. (492)

Jewelry Under the Furniture

Robin pretends that a “bangle” rolled under a piece of furniture in Geraint Winn’s office in Lethal White as Venetia Hall to create an explanation for her planting a listening device there (166-167).

In Running Grave, Becca Pirbright, almost certainly with Mama Mazu’s cooperation planted the mother-of-pearl Jesus fish necklace under Rowena’s bed in Chapman Hall to entrap her as a thief (529).

Eavesdropping on the Quarreling Couple

Robin plants another listening device in Lethal White, this time a smart phone in a shop, to eavesdrop electronically on Jimmy Knight and Flick (404). In Running Grave, she hides behind a Chapman Farm Portakabin to eavesdrop the old-fashioned way on the intense conversation between Emily and Becca Pirbright (450-452).

Illegal Bugs

Having noted the illegal bug that Robin planted in Winn’s office in Lethal White and the stray smart phone recorder, I am obliged to list the illegal device that Mitch Patterson’s Agency planted in the offices of Andrew Honbold QC, an exercise that resulted in Patterson’s arrest (729). It is funny that there is no comment made during the High Five celebration of Patterson’s downfall, that, if Robin-Venetia had been caught in Winn’s office or the device found, she’d be in jail, too.

Fighting in the Streets

Strike, Midge, and Barclay mix it up in the street at night with the Frankenstein brothers in Running Grave who were attempting to kidnap their client, Tasha Mayo (664-666). That was exciting but it had little of the drama and atmosphere of Strike’s solo takedown of Jimmy Knight in Lethal White the night of the Paralympics Ball, a fight in a rowdy crowd patrolled by police (264). Strike escapes the scene to meet up with Robin immediately after each brawl.

Strike’s Latin

Cormoran has a remarkable facility with Latin, which comes up in Lethal White when Chiswell quotes Catullus at Aamir and Raff at Westminster (453). He actually explains to Amelia Crichton his interest and skills in Classics at the end of Running Grave (936).

Boogeymen

Jack o’Kent in Lethal White and the Drowned Prophet in Running Grave, I think, both qualify as haunting figures with which to scare small children and cult members. ‘Jack o’Kent’ was Jasper Chiswell’s nickname for the worker on his estate, the father of Jimmy and Billy Knight, and he was right out of Grimm’s. Raff describes him as having “something to do with the devil” per his moniker: “Scared the hell out of me when I was a kid. He had a kind of sunken face and mad eyes and he used to loom out of nowhere when I was in the gardens. He never said a word except to swear at me if I got in his way” (243).

Mazu qualifies as a Halloween figure wannabe as well; Rowling describes her “as the demon of fairy tales, the witch in the gingerbread cottage, mistress of agony and death, and she stirred in Robin the shameful, primitive fears of childhood” (905). The boogey of the Drowned Prophet lives forever in the minds of UHC initiates, too.

Sacha Legard!

Strike remembers Sasha Lagard, one of Charlotte’s siblings, when he is at the horse racing track in Lethal White; the last time he’d been there had been in a party that included Charlotte and Sacha (546). He pops up again in Running Grave in a Charlotte obituary:

‘We’ve lost the funniest, cleverest, most original woman any of us knew,’ said Campbell’s half-brother, actor Sacha Legard, in a separate statement. ‘I’m just one of the heartbroken people who loved her, struggling to comprehend the fact that we’ll never hear her laugh again. Death lies on her like an untimely frost Upon the sweetest flower of all the field.’ (487, cf 512)

I have reason to think, beyond his quoting from the closing scene of Romeo and Juliet, a wonderful alchemical drama, that we’ll be hearing a lot about boy Sacha, for reasons Nick Jeffery is going to lay out tomorrow in his post here. I’ll leave this hint: Sacha Legard is named as ‘Simon Legard’ in Troubled Blood (673), the only other time he is referenced in the series besides Strikes 4 and 7. It is NOT a good sign in anything written by Rowling to be a ‘Simon.’

Gun-Pistol-Rifle Gaffes

In Lethal White, Strike takes a “revolver,” a “Harrington & Richardson 7-shot” according to the detective, from Kinvara at the Chiswell manor (585). It reappears again in the climactic confrontation between Robin and Raff, in which meeting he holds the revolver barrel pressed against her forehead (619, see ‘Third Eye’ above). As Strike leaves the manor with the revolver, the weapon is referred to as a “rifle.” Technically, beyond the vernacular usage of ‘rifle’ for a long-barreled weapon and ‘gun’ for hand-guns, it is possible that the revolver had a rifled barrel; that is extremely unlikely given the age of the weapon in question. See ‘Lethal White: Flints and Head Scratchers’ for a longer discussion of the absurdity of this weapon and how it is described in Strike4. For this list, just note that Rowling-Galbraith refers to a revolver as a rifle.

In the Temple fight between Robin and Mazu at the end of Running Grave, the weapon in play is a “rifle.” It is referred too as a rifle nine times in this passage. The problem in parallel with Lethal White is that it is also called a “gun” five times. A long barreled firearm as this obviously is can be either a rifle or a gun, depending on whether the bore is smooth or grooved (‘rifling’). It cannot be both. Given Rowling’s crew of readers include at least two with military experience, this kind of carelessness is surprising. It is, however, a fun parallel between Strikes 4 and 7. Points for consistency, even in the gaffes.

Strike’s PTSD in Cars

In the Lethal White conversation on the verge, Strike spells out his issues with being a passenger after the vehicle he was in was blown up by an IED in Afghanistan:

“After I got blown up, I couldn’t get in a car without doing what you’ve just done, panicking and breaking out in a cold sweat and half suffocating. For a while I’d do anything to avoid being driven by someone else. I’ve still got problems with it, to tell the truth.”

“I didn’t realize,” said Robin. “You don’t show it.”

“Yeah, well, you’re the best driver I know. You should see me with my bloody sister.” (543)

Strike’s Running Grave experience in the BMW when he, Robin, and Will are being chased by a Ford with a driver taking shots at them is an unpleasant one, as expert a driver as Robin proves to be once again. He clearly is having flashbacks:

A third shot: this time wide.

‘Hold on!’ Robin said again, and she skidded around the turn into the other lane, making it by inches, causing Strike to smash his face into the intact side window.

‘Sorry, sorry—’

‘Fuck that, GO!’

The passing bullet had flooded Strike’s brain with white-hot panic; he had the irrational conviction that the car was about to explode. Craning around in his seat, he saw the Ford hit the barrier at speed. (843)

The narrator reports in the next chapter that “it had taken an hour for Strike’s heart rate to slow to an appropriate rate for a stationary forty-one-year-old male” (845). I’m calling that a “panic attack” consequent to PTSD because of the “irrational; conviction that the car was going to explode.”

Strike Yelling at Subcontractors

Cormoran loses it with Andy Hutchins in Lethal White when he calls to tell Strike that his MS has flared and he is “having trouble walking.” Strike responds unsympathetically with “I know the fucking feeling!” and calls him a “stupid fucker!” in a rage (256). He snaps at Robin once, too (“Do as you’re bloody told!” 452), but it’s the subcontractor who got both barrels (smoothbore).

Midge Greenstreet is the contractor who Strike lashes out on in Running Grave. He gets after her over the phone for being inside Tasha Mayo’s house in barely repressed anger (565) and then snaps at her again when Tasha blows the Dr Zhou mission to rescue Lin (825).

No See, No Speak

After Raff is arrested, according to Izzie in the Lethal White epilogue, he does not “want to see anyone” (639). Mama Mazu in jail at the end of Running Grave does him one (or two?) better. Strike reports that the Met has told him she “hasn’t spoken a word since her arrest,” not even to lawyers, a ploy Robin attributes to a power play,” a bid for control (931).

Elders to London for Care

Geraint and Della Winn in Lethal White had moved their mothers to London from Wales when they could no longer care for themselves (475). Strike and Lucy are working to do the same thing throughout Running Grave.

Conclusions

Is there more? I’m sure of it. In addition to all the White-Grave correspondences I missed, there are the as interesting Cuckoo-White-Grave 1-4-7 parallels that really make the series axis stand up. The one that comes immediately to mind is that siblings who do not share a mother and father are at risk of becoming victims or murderers in Strike-World: Lula, Charlie, and Daiyu buy the father at the hand of their insane step-brother or sister, and John, Raff, and Abigail become who they are because of what Freud called their “family romance,” the dynamics of not being loved by a mother or a father.

Another is that suicide should always be assumed to be murder because, even when the the person topping themselves actually does the deed (unlike Lula, Jasper, and at least three of the suicides in Running Grave, about which speculative idea, more in a minute), they are killed by the agents who drove him or her to it. See Deeby Mac in Cuckoo:

… Lula Landry’s suicide?’ said the interviewer, who was English.

‘That was fucked-up, man, that was fucked-up,’ replied Deeby, running his hand over his smooth head. His voice was soft, deep and hoarse, with the very faintest trace of a lisp. ‘That’s what they do to success: they hunt you down, they tear you down. That’s what envy does, my friend. The motherfuckin’ press chased her out that window. Let her rest in peace, I say. She’s getting peace right now.’ (63)

Why Rowling would have made these two ideas the heart of the seven book series’ surface mysteries will be the subject of future posts.

With that pledge I’m going to call it a night! Tomorrow I hope to write up the remaining series correspondences that need to be checked now that we have the seventh book, those between Career of Evil and Running Grave, and my conclusions, all of which turn around why I think there is a real benefit for Rowling Readers, despite it being obviously wrong, to think of the Strike-Ellacott series as officially closed with the publication of Strike7.

See you then!

As soon as I sent this and started the (C) or third part of this post, I had several parallels come to mind. I won't be revisiting this White-Grave subject in a separate post anytime soon so I'll post them here in the comment boxes and continue to put more here as they surface.

Feel free to join in or add your objections. I haven't checked with anything like deliberate review to see if the correspondences I've noted between Strikes 4 and 7 don't also occur in other books; if they exist, that undermines the 4-7 relationship's validity in not being exclusive. Are there 'third eyes' in the other five books? I don't know!

Here are three correspondences I missed in the first review --

(1) Failed Pregnancy Trap: the foundation crime of 'Lethal White' is the pregnancy trap that Ornella Seraphin sprung on Jasper Chiswell. A baby resulted but no marriage, which, as with the Leda Strike-Jonny Rokeby trap, meant that it was, as Raff put it, a "gamble that didn't work out." That's a great 1-4 link, but Bijou's effort to win (force?) a QC's hand via pregnancy so far is taking the Chiswell route, i.e., blowing up Hunbold's marriage but not yet gaining her a ring (she needs to take a few lessons from Sarah Shadlock). Of course, if it's Strike's baby -- and I think it is -- then she's in for even more of a hard time.

(2) One Night Stand 'Displacement Fucks:' Speaking of Belinda Watkins, Esq., she is part of another 1-4-7 trio, joining Ciarra Porter, whom Strike lands in 'Cuckoo' to assuage his grief and anger about Charlotte's engagement, and Coco the Red Head-Hot Mama in 'White,' whom Strike scores to get over Robin's decision to go on her honeymoon.

(3) Sacraments: I confess to slapping my forehead in neglecting to note that the books each begin with a Christian ceremony and sacrament, 'White' with a wedding and 'Grave' with a baptism. Robin and Strike are the center of attention in both -- and Strike walks away from each with no little frustration about not being his business partner's conjugal mate. The 1-4-7 piece would be the funerals of 'Cuckoo' for Lula Landry and Rochelle Onifade, making the sequence work in reverse; Christians normally head through life beginning with child baptism, a wedding as adults, and a burial with rites after death.

I'm really fascinated by the idea of the foundation crime. If the HP series foundation crime is Merope Gaunt's coercive love with a love potion which gives rise to Lord Voldemort, a villain who sought immortality by killing others, then shouldn't the foundation crime in the Strike series also give rise to a villain who undoubtedly learned how to manipulate others from a family of corrupt and ancient nobility not unlike the Gaunts? My money's on Charlotte as the Voldemort of the Strike series because of her tactics, and I wonder if Sir Anthony had some way of coercing Charlotte's mother into marrying him...

Also in reading about the Campbells, I found 2 interesting women. Muriel Caddel was kidnapped by the Campbells, and at the age of 12 (!) married Sir John Campbell. Later their grandson (another John Campbell) sold Croy (!) which enabled him to purchase the island of Islay. Port Charlotte of Islay was named after Lady Charlotte Campbell who kept a diary (!) when she was lady in waiting to Caroline, Princess of Wales. In addition to the diary, she wrote several publications, among them The Manoeuvoring Mother and The Wilfulness of Woman. The crime against Muriel and her marriage at 12 years is actual history, not an aspect of writing a very complicated and engaging story. But it makes me wonder about Sir Anthony and if, as you hint at, Charlotte's suicide was staged by her half brother Sacha, what will the Strike and Ellacott Agency be asked to do next? Who will reach out? Amelia?