J. K. Rowling tweeted earlier this year that all of the epigraphs in her seventh Strike novel, The Running Grave, will be from the I Ching. We know this is not technically true, just to be clear, because the manuscript we have been shown has a passage from Dylan Thomas as an opening epigraph; one has to think, though, that these Thomas lines are an outlier and all the other epigraphs will be from the classical Chinese book of divination (cf., the opening epigraphs of Troubled Blood with its one passage from Aleister Crowley and all the rest from Faerie Queen).

The choice of the I Ching is a fascinating one and consistent with Rowling’s previous sources for her epigraph material in having been as unpredictable as the others; from classical poets and pundits, Jacobean Revenge dramas, and Blue Oyster cult lyrics to Ibsen’s Rosmersholm, Spenser’s Faerie Queene, and Victorian Women’s poetry, not to mention Gray’s Anatomy!), none of Galbraith’s book and chapter cue sources were logical or obvious to her millions of readers.

The I Ching differs from these other sources, however, in being announced in advance rather than just being hinted at in a book’s title or in images the author used on her Twitter home-page header. Why she chose to make this revelation is of course known only to herself. Obvious guesses include that she thinks it especially important, that fandom focus on Dylan Thomas’ poetry was mislaid, and that her most serious readers, if they are to ‘get’ the meaning and use of this divinatory material in Running Grave, need and deserve a head-start or fair warning.

Though I was enjoying reading Dylan Thomas’ work and about his life and poetry, I have collected four copies of I Ching translations, a ‘biography’ of the text used in a Beatrice Groves post on the subject, and, believe it or not, a bundle of yarrow stalks. I bought the sticks after a bizarre experience, the reason I purchased a third and fourth translation of the original Chinese text, which made me think I really needed to take this project more seriously.

As readers here know, I work in an upscale grocery store, a company for whom I have worked since 1996 off and on in Houston, Philadelphia, and Oklahoma City. It pays the bills, provides scheduling flexibility for speaking dates, my co-workers and our customers as a rule with few exceptions are a delight, and I get a 30% discount on food. I bring in my lunch, a meal prepared by my wife, and am given half and hour each shift in which to enjoy that. When I want to eat alone with my thoughts or a good book, I sit down upstairs in what was once the Human Resources office but which has now become a storage room with a desk.

Two weeks ago I had an odd moment in that private dining room.

There are stacks of books on the floor there that are leftovers from when the store’s HR leaders had a small library of diet and leadership texts and DVDs that workers were encouraged to read or watch (the incentive was $25 if they wrote a one page review of their take-aways from that reading or viewing). Not being shelved horizontally but stacked vertically on the floor so only the top titles of each stack were visible, I couldn’t see the spines and didn’t take the trouble to look through them.

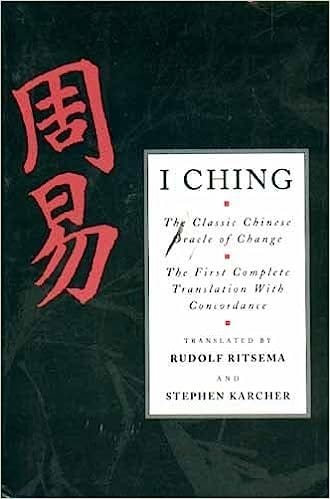

On this day, though, someone else who visited the office had knocked a stack over. Beneath a copy of Supersize Me, a New Age leadership text, and a five volume set of Twilight series knock-offs, I saw something I never would have expected: a worn, water-damaged, paperback edition of the I Ching, the translation by noted Jungian scholar Rudolf Ritsema and the American mytho-sinologist Stephen Karcher. I picked up the 816 page tome and enjoyed the introduction while inhaling the meal Mary had cooked for me.

There are several ways to describe this sort of encounter out-of-nowhere. For most, to include the fictional characters of Strike and Ellacott, it would be described, ‘dismissed’ really, as a coincidence, a meaningless chance encounter. To the Jungian analyst, though, it would be an instance of ‘synchronicity,’ the coinciding appearance of a person, idea, or thing in keeping with the subject’s mental state, more of a revelation.

A sinologist in contrast might offer the Buddhist aphorism, ‘When the student is ready, the teacher appears.’ I did not know what to make of Rowling’s unprecedented full-throat announcement of the I Ching as her epigraph source or of the avalanche of pointers to Carl Jung she had made from Troubled Blood forward. So the Oracle appeared in the shape of a Jungian translation of the I Ching, an out of print Element first edition, in an Oklahoma grocery store’s back office? You tell me.

What I will share with you is the heart of this book’s perspective on the I Ching and its proper use in divination, something, as you probably expect, well removed from Professor Trelawney’s Hogwarts classroom. It points I think to a possible use Rowling’s epigraphs will serve in Running Grave and to a key and neglected component of Strike’s story arc and transformation, namely, his transcendence of his lifelong resistance to a committed relationship with a woman and his ‘Team Rational’ hostility to a spiritual dimension in human life.

The Rudolf Ritsema Introduction to I Ching

If the 8th of May is a pivotal date in Running Grave, we might guess that Rowling is a student of Ritsema’s I Ching because, beyond being Victory Europe or ‘VE’ Day, the actual day in 1945 was the day the translator and his wife chose to be married, exactly one year later they moved from their safe-space in Switzerland back to the Netherlands, and the author died on that date in 2006. Somehow that seems appropriate for the man who made the Eranos Foundation, not to mention esoteric study of I Ching, what it was; the day in which global military conflicts were brought to resolution (of sorts) was the time in which he contracted the greatest resolution of contraries and made his transition to the next life.

I think Ritsema and Karcher’s translation of I Ching may be important for understanding Rowling’s use of the divinatory classic in Running Grave because of the perspective employed, one with a traditional understanding of imagination, of heart, of soul and spirit, and even of magic. I will quote from Ritsema’s introduction to the book at some length to point out these ideas, all of which run parallel with Rowling’s ideas as evident in her interview remarks through the years, her Harvard convocation address, and her use of Faerie Queene and Victorian women poet epigraphs in her Strike novels. All of them are mentioned in Ritsema’s opening salvo about what the I Ching is and why it is important:

The I Ching offers a way to see into difficult situations, particularly those emotionally charged ones where rational knowledge fails us yet we are called upon to decide and act. It gives voice to a spirit concerned with how we can best live as individuals in contact with both inner and outer worlds.

The I Ching is able to do this because it is an oracle. It is a particular kind of imaginative space set off for a dialogue with the gods or spirits, the creative basis of experience now called the unconscious. An oracle translates a problem or question brought to it into an image language like that of dreams. It changes the way you experience the situation in order to connect you with the inner forces that are shaping it. The oracle’s images dissolve what is blocking the connection, making the spirits available….

Consulting an oracle and seeing yourself in terms of the symbols or magic spells it presents is a way of contacting what has been repressed in the creation of the modern world. It puts you back into what the ancients called the sea of soul by giving advice on attitudes and actions that lead to the experience of imaginative meaning. Oracular consultation insists on the importance of imagination. It is the heart of magic through which the living world speaks to you. The modern interest in alternative cultures and the old ways is a reflection of our need to recover this heart of magic, for it is the way our inner being speaks, thinks and acts. (p 8)

This association of heart, magic, imagination, the soul, and the “inner being” of a person, traditionally the logos within, is a remarkable summary of Rowling’s core ‘spiritual not religious’ beliefs that I have inferred from the author’s work and public comments over the last twenty plus years.

Ritsema’s discussion of how to receive the Oracle’s response to a question, too, is resonant with Rowling’s comments about the magic elision of minds between a reader and author in imaginative fiction and her own use of traditional symbols to foster this experience of the transcendent. His discussion of the Te or Tao in the I Ching, especially the I of the cosmos and the individual, echoes the discussion of the heart and logos in Rowling’s use of Estecean-inspired poetry in Ink Black Heart.

The act of consultation is based upon chance, the random division of a set of 50 yarrow stalks or throwing and counting three coins six times. This chance event empowers a spirit beyond conscious control. It gives the forces behind your situation the chance to speak by singling out one or more of the book’s symbols. Through this procedure, what you see as a problem to be mastered becomes a sign or symbolic occurrence that links you with another world. Like a shaman’s drum and dance, these symbols can speak to you on many levels, beginning a creative process which, in traditional terms, completes the ceaseless activity of heaven. This is religion at its fundamental level. It reflects a sense of spirit that unites the great and the small, a spirit that moves in each individual….

The term emphasizes imagination, openness and fluidity. It suggests the ability to change direction quickly and the use of a variety of imaginative stances to mirror the variety of being. The most adequate English translation of this is versatility, the ability to remain available to and be moved by the unforeseen demands of time, fate and psyche. This term interweaves the I of the cosmos, the I of the book, and your own I, if you use it.

I in the human world is understood in terms of three other themes, tao, te, and chun tzu. Tao, literally way, is the flow or stream of creative energy that makes life possible, the say in which everything happens and the way on which everything happens. Te, often translated as power or virtue, refers to the power to realize tao in action, to become what you are meant to be. A chun tzu is someone who seeks to acquire te through invitations to a dialogue with the way, its power and its virtue. What the chun tzu finds through this dialogue is significance, the experience of spirit, meaning and connection. (Pp 9-10)

Ritsema then describes what I think is the most likely transformation we are to see in Cormoran Strike because of his Running Grave experiences: a change in his understanding of himself and the world consequent to “the hidden complement or shadow” in his life being revealed, his having to hear the “voice” or logos of what his “ego has rejected” hearing. Strike7 promises to include, per the Parallel Series Idea, its fair share of revelations about Strike’s past, especially with respect to Leda Strike’s death and the childhood experiences that immunized him to all spiritual experience or worship. The heart, if you will, of those ‘reveals’ will be the light thrown in the Shadow of his soul.

The idea that words, things and events can become omens that open communication with a spirit-world is based on an insight into the way the psyche works – that in every symptom, conflict or problem we experience there is a spirit trying to communicate with us. Each encounter with trouble is an opening to this spirit, usually opposed by the ego because it wants to enforce its will on the world. Divination gives a voice to what the ego has rejected. It brings up the hidden complement or shadow of the situation in order to link you with the myths and spirits behind it. This changes the way you see yourself, your situation and the world around you. (Pp. 10,11)

Rowling, if I am right in this, will be using the I Ching symbolism in Running Grave as well as her mythological tropes and alchemical artistry, to create what Ritsema describes as “fish traps” for the spirit to be caught in the hearts of her readers.

Thus divination is not an ideology or a belief but a creative way of contacting the spirit. It is imagination perceiving forces and inventing ways to deal with them. This involves a combination of analysis and intuition that normal thinking usually keeps apart. This process values imagination and creativity. It shifts the way you make decisions.

Opening this space, where identity becomes fluid and the spirits involve themselves in your life, is the purpose of divination. Using a divinatory system is an exploration of the unconscious side of a situation. The symbols evoked adjust the balance between you and the unknown forces behind it.

The language is the key to the contact. The words are, as the Chinese say, “fish-traps” for spirit or tao. (11)

How, then, are Rowling’s serious readers to contemplate the text of Running Grave? My first thought is that she wants us as always to enjoy the story with all its twists and turns, dead-ends and resolutions — and then to contemplate on its symbolism and richer meaning, the soul’s journey to self-awareness, intellect becoming attuned to the Tao, and its perfection in Spirit. Ritsema describes how the adept ‘interprets’ the revelations of the Oracle in an I Ching reading:

According to this tradition, the function of the I is to provide symbols (Hsiang). The text came into existence through a mysterious mode of imaginative induction, also called Hsiang, which endows things with symbolic significance. Acted upon simultaneously by figures in heaven, patterns on earth and events in the psyche, the old shamans and magicians spontaneously Hsiang-ed or symbolized to form the texts and figures as links to important spirits and energies.

The chun tzu, the ideal user of the book, can take advantage of this fundamental spirit power. He or she observes the figure obtained through divination and takes joy in its words, turning and rolling them in the heart. These words translate or symbolize (hsian) the situation, connecting it with the level of reality from which the symbols flow. Through this action, the chun tzu becomes Hsiang or symbolizing, linking the divinatory tools and the spirits connected with I directly to the ruling power of the personality. To do this is called shen, which refers to whatever is numinous. Spiritually potent.

Like the shamans and sages of old, this tradition maintains, the person who uses these symbols to connect with I will have access to the numinous world and acquire a helping-spirit, a shen. The I Ching is more than a spirit, it channels or connects you to spirit. It puts its users in a position to create and experience their own spirit as a point of connection with the forces that govern the world. It is this imaginative power that was elaborated, re-interpreted and defined throughout later Chinese history as the basis of philosophy, morals and ethic. It is a way to connect with the creative imagination that underlies all systems and creeds. (14)

On the HogwartsProfessor back-channels, I asked if anyone of that Royal Society of Rowling Readers had any questions about Running Grave I could ask the Oracle via my newly acquired yarrow stalks. Why not, I thought, ask the divinatory source of Rowling’s epigraphs what her story would reveal? The first answer I received, almost certainly tongue in cheek given Rowling’s aversion to online fandom’s preoccupation with Strike-Ellacott ‘shipping, was “Will they kiss?”

Just how far off I was in the sort of questions you ask the Oracle and my respondent was in that question, is evident in Ritsema’s discussion of consulting the I Ching. This is much more a meditative exercise than a visit to Professor Trelawney for a tarot card reading. ‘Yes or No’ questions just won’t work here:

Making a question has two parts. The first part is soul-searching. Search out the feelings, images and experiences that lie behind the immediate situation – what you feel, remember, are afraid of, what you think the effects of the problem might be, what it symbolizes for you, what relations and issues it involves, what is at stake, why you are uncertain or anxious about making a decision. This establishes the subjective field. The answer will focus on these concerns. Talking to someone about the situation can often help you bring these things out and clarify them.

This leads to the second step – a clear formulation of the question based on what you want to do in the situation. Be precise. Examine what you want to do with as much honesty and awareness as you can. And, if possible, come to a conclusion, presenting it as a question: “What about doing this?” “What will happen if I…?” “What should my attitude be toward …?” The Oracle will connect you with an archetypal image through this question. This clarifies the dynamic forces at work in your psyche, the seeds of future events.

This process allows you to break through the wall that usually separates you from the spirit world beyond your immediate control. The response will not be a simple yes-or-no answer, though it will include specific advice so be open to a surprise. What you are really asking for is an understanding in depth upon which you can base your decisions and actions. The question is the precise point of contact with the unknown, and it enables you to open and focus the divinatory space. It is part of a process of expansion and contraction that leads from an unconscious relation with a disturbing force to specific advice on how to handle the situation. (18)

Which explains why I won’t be asking the Oracle if Strike and Ellacott shack up, become engaged, or just kiss in Running Grave.

It also points, obliquely I’ll grant you, to Rowling’s perspective on the divinatory arts and their links to the experience, crafted by the oracle-cum-artist, had by thoughtful readers via their logos-imagination in a text laden with “fish-traps” for the soul to capture the Tao. If each part of the book and every chapter is prefaced with a hexagram-epigraph, not to mention the possibility that the novel itself will include a divination or two a la Troubled Blood’s several embedded tarot card spreads, the serious reader will be confronted with material for several months of reflection and meditation.

Hi John,

Thank you for sharing your thoughts. As you perhaps consider yourself a Rowling geek (saying that in the most positive way), I consider myself a Yijing geek. Fascinating your first encounter with the Yijing was through the Ritsema/Karcher's translation as it is quite unyielding for a beginner in the way it was translated and presented. Not a volume that I would use for divination, for example, but perhaps for reference. There's an interesting story regarding that collaboration, one that ended in enmity between them. Eranos later revised the translation and in 2005 it was published by Watkins under the Ritsema/Sabaddini name (see here for a review and some background https://www.biroco.com/yijing/ritsema.htm). I could go on but it would be irrelevant to your note...

Now, Rowling didn't use Ritsema/Karcher for her epigraphs but the Wilhelm/Baynes translation. That is, if we go by what was shared by you in "First ‘Running Grave’ Epigraphs Out: Dylan Thomas Poem and I Ching Note" back in February. The complete quote is as follow:

"A house that heaps good upon good is sure to have an abundance of blessings. A house that heaps evil upon evil is sure to have an abundance of ills. Where a servant murders his master, where a son murders his father, the causes do not lie between the morning and evening of one day. It took a long time for things to go so far. It came about because things that should have been stopped were not stopped soon enough.

In the Book of Changes it is said: “When there is hoarfrost underfoot, solid ice is not far off.” This shows how far things go when they are allowed to run on."

It comes from the Wenyan Zhuan, one of the Ten Wings of the canonized Yijing and its brief text applies only to the first two hexagrams, in this case, the text of hexagram #2, Kun or The Receptive.

If you haven't, I strongly suggest you find a copy of that translation as it appears to be the one Rowling used. Mind you, I've only seen one quote/epigraph, the one you shared, and doesn't mean the rest are from the same translation but it would make more sense if they did for consistency.

Best wishes.

Thanks as always John for the insightful analysis of one of the influences for JKR/RG. Something I have wondered is whether JKR/RG’s own duality of personality--being herself and RG--and her own personal longing for wholeness might be coming into play in Strike’s own journey? Particularly since JKR has referenced her own journey as being pivotal for the HP series, wouldn’t be surprised if the Strike novels are just a front row seat for us as readers to watch her own transformation during this part of her life...