Reading Rowling the Hard, Right Way versus Enjoying the Surface Story and Discussing Themes

Images of the Transfiguration, Story as Non Liturgical Sacred Art, What We Do at Hogwarts Professor, and How We'll Be Reading Hallmarked Man

Tuesday was the Feast of the Transfiguration, one of the Great Feasts of the Orthodox Christian liturgical calendar, and it was a perfect time for me to write out what makes a great story-teller ‘great’ and a serious reader one who gets its depths and interior meaning beyond the surface-story icing on the cake.

Let’s start with two representations of the Transfiguration of Christ, one a painting that played an important role in my transformation as a young man and the other the traditional icon used in right-believing (ortho-dox) worship. Both are beautiful in their ways; one is sacred art and the other secular art with a religious subject. That distinction is right at the crux, believe it or not, of either just loving J. K. Rowling’s novels or grasping the artistry and meaning of her work, why she is the writer with the greatest impact on her readers in our age as well as the one with the largest and most dedicated global audience.

Let’s start with the modern and much more famous depiction of Christ’s Transfiguration, Raphael’s last and many believe best painting, ‘The Transfiguration of Christ,’ 1516-1520:

I love this painting, not only because of the extraordinary artistry and edifying power of the choices made by Raphael, but also because how one of my mentors at the University of Chicago used it to explode my ideas of art, faith, and story.

Long story short, in 1979 Polaroid using their room-sized ‘Camera Camera’ took pictures of Raphael’s masterpiece to create a 95% scale reproduction of the original 13’ by 9’ canvas. That life-sized color photograph and a collection of greater-than-original close-ups became an exhibit that toured Europe and the United States, an exhibit that no doubt sold a few of Polaroid’s ground-breaking (and storage space busting) cameras. It also brought an experience of perhaps the most famous piece of religious art in the Western canon to thousands who could never make a trip to the Vatican Library to see the original.

I was one of those people.

I tagged along with Jeff Bond who was going to see it at the exhibition held at the University of Chicago’s Smart Gallery; I had no interest in painting, in Christianity, truth be told, though I was nominally a believer, or in art history. I knew, though, that Bond, then a graduate student in political philosophy at the University, was the most challenging and table-flipping thinker I’d ever met. If he wanted to go look at an old painting, I was not going to miss his throw away observations at the exhibit.

Good choice.

The Smart Gallery had set out marble seats much like those at the Art Institute in downtown Chicago where visitors could sit and meditate on the painting displayed. I thought of it as a photograph, which of course this picture was in fact, but, more to the point, because I thought of all paintings as just primitive photography, more or less. Between the time of my sitting down next to Bond in front of The Transfiguration and our getting up an hour or so later, that pedestrian prejudice was history.

I won’t bore with you everything Bond said in his Socratic discussion of what he was seeing, thinking, and wondering about; I won’t because I cannot remember in it in any detail. As a political philosopher, I do remember Bond the neo-Straussian noted that all the events depicted took place well outside the city and that Raphael depicted Moses and Elijah, the Law and the Prophets, with written work, while Christ Himself was not.

I can’t be sure that Bond was deliberately aiming those points at me, but, book-consumed Classics student and Student Government President that I was, the reigning opinions in the city and in academic authority were my guideposts rather than anything spiritual or religious. Aimed or not, those were direct hits.

More important, however, was his reading of the painting as a story of relationship, hierarchy, and perspective; he saw things that were obvious to me after he pointed them out — usually in the form of questions like, “What do you think the Apostles are thinking and saying to one another and to the father?” — but which would have been invisible to me without his guidance. There were layers upon layers of meaning in the artist’s deliberate or Shed conjunction of two seemingly distinct and separate events shared in the Gospel according to St Matthew and St Mark:

Raphael's painting depicts two consecutive, but distinct, biblical narratives from the Gospel of Matthew, also related in the Gospel of Mark. In the first, the Transfiguration of Christ itself, Moses and Elijah appear before the transfigured Christ with Peter, James and John looking on (Matthew 17:1–9; Mark 9:2–13). In the second, the Apostles fail to cure a boy from demons and await the return of Christ (Matthew 17:14–21; Mark 9:14).

Bond’s point may seem obvious to you — that Raphael’s decision to portray these events simultaneously was at the heart of what he was trying to say to Christian believers in worship and to the world at large (the painting was commissioned as an altar piece) — but it laid bare to me the childishness of my beliefs about paintings and all art, namely, that they were all more or less mindless exercises in craft to entertain an audience with one’s skills.

My vision wasn’t transformed in that afternoon at the gallery exhibit, far from it, but my need for a new mindset and way of seeing was exposed so clearly that even I could not ignore it. The ocean liner of my thinking began it’s long, years long u-turn from the conventional conveyor belt of ideas to a more traditional or theocentric idea of art.

The biggest step in that journey, I think now, was reading the Perennialists, a group of writers that Bond urged me to read but whose work, oddly enough, we never discussed. Except for the world-upside-down ideas of the Traditionalists about art and story, I never become an Orthodox Christian and there certainly is no ‘Hogwarts Professor.’

Before we look at and discuss the icon of the Transfiguration, then, and contrast it with Raphael’s painting, let me share the high points of Perennialist thinking about art as such and why it matters when reading the stories of J. K. Rowling.

Perennialism and Sacred Art

Rowling is a story writer and an intentional craftsman. As such, she is an artist. It is essential, consequently, in you want to grasp the utility of the traditionalist perspective as a tool to explore her work, to understand this school's view of the place and function of art in human life. As you’d expect if you know anything about their defining beliefs with respect to symbolism, their understanding of art is radically different than the prevalent opinion today.

The conventional position is that good art as opposed to bad art is a necessarily subjective distinction about an author's success in expressing his internal inspiration and ‘touching’ or ‘reaching’ his audience. Art is understood to be for "art's sake," that is, not of any practical utility other than as a tool for expression and reflection. As the personal creation of the artist, however moral or immoral its meaning may be, it is in essence individual and subjective with respect to what is true or real rather than an objective statement of same.

As James Cutsinger explained Frithjof Schuon's view of this, today

good art is a function of two things alone: the sincerity, originality, and intensity of the artist's perception, and the degree to which he is able to evoke in his audience a kind of sympathy by giving form to their own moods, expectations, or emotional needs.... The expression of an artist's feelings or personal experience [from this view] and the individual preferences of those who encounter his work are the sole determinates of what we may call its goodness or badness.... (Cutsinger 1998, 124).

The Perennialist concern with art, in contrast, is less about gauging an artist's success in expressing his or her perception or its audience's response than with its conformity to traditional rules and its utility, both in the sense of practical everyday use and in being a means by which to be more human. Insofar as a work of art is good, it is "sacred art;" so much as it fails, it is "profane." The best of modern art, even that with religious subject matter or superficially beautiful and in that respect edifying, is from this view necessarily profane.

Sacred art is art which points us toward God through the force of a quality or energy inherent in the form of the art itself, and independently of both the artist's individuality and our own personal likings or sympathies. It is intrinsically linked to the very structure of the universe, and it thus represents "an adequation to the Real." The Beauty of sacred art is no less objective than the Truth of metaphysical doctrine, the only difference being that "what the intelligence perceives quasi-mathematically, the soul senses in a musical manner that is both moral and aesthetic; it is immobilized and at the same time vivified by the message of blessed eternity that the sacred transmits" (Cutsinger 1998, 124; citing Schuon 1982, 103).

Art, then, is not for "art's sake," but for use in the daily struggle to transcend the world. "Art is for the sake of life itself."

In a traditional civilization in which all activity is based on principles of an ultimately Divine Origin, the making of things or art in its vast sense is no exception. In such civilizations all art is traditional art related at once to the necessities of life and spiritual needs of the user of the art as well as the inner realization of the artist who is also an artisan. There is no distinction between the arts and crafts or fine arts and industrial arts. Nor is there a tension or opposition between beauty and utility. Art is not for art's sake but for the sake of life itself.

Art in fact is none other than life, integrated into the very rhythm of daily existence and not confined to the segregated space of museums or rare moments of the annual calendar. In a traditional civilization, not only is art traditional art but also what is called religious art in modern parlance shares the same principles with the art of making pots for cooking or weaving cloth to make a dress. There is no distinction between the sacred and the profane both of which are embraced by the unifying principles and share the symbols of the tradition in question (Nasr 2006, 178).

Art which conforms to "traditional principles," revealing the archetypes in visible forms, is inherently beautiful and useful, simultaneously, as the poet says, the "splendour of the true" and helpful along the way of the soul's journey to union with Spirit. It is "for man's sake" or ultimately "for God."

Traditional art... is functional in the most profound sense of this term, namely, that it is made for a particular use, whether it be the worshiping of God in a liturgical act or the eating of a meal. It is, therefore, utilitarian but not with the limited meaning of utility identified with purely earthly man in mind. Its utility concerns pontifical man [bridging heaven and earth] for whom beauty is as essential a dimension of life and need as the house that shelters man during the winter cold. There is no place here for such an idea as "art for art's sake," and traditional civilizations have never had museums nor ever produced a work of art just for itself.

Traditional art might be said to be based on the idea of art for man's sake, which, in the traditional context where man is God's viceregent on earth, the axial being on this plane of reality, means ultimately art for God's sake, for to make something for man as a theomorphic being is to make it for God. In traditional art there is a blending of beauty and utility which makes of every object of traditional art, provided it belongs to a thriving traditional civilization not in the stage of decay, something at once useful and beautiful. (Nasr, S. H. 2007, 204)

As Marco Pallis wrote about traditional art in Tibet, sacred art is in essence "intellectual rather than aesthetic,"[1] human creativity in service to "the attainment of metaphysical Knowledge" (Pallis 1949, 351-352). The artisan's success in this regard is gauged in its audience's being reminded of their divine origin and end and by its engaging and fostering their noetic perception.

'Remembering In a World of Forgetting'[2]

Coomaraswamy, the Perennialist who wrote most frequently about how best to understand art and to whom all other traditionalists refer and defer, asserted that "works of art are reminders; in other words supports of contemplation,"[3] that is, "a real art is one of symbolic and significant representation; a representation of things that cannot be seen except by the intellect" (Coomaraswamy 1956, 10-11). Sacred art is "ultimately a gift from Heaven and a channel of grace which brings about the recollection of the Spirit and leads us back to the Divine" (Nasr 2006, 175). This recollection is an essential "assist in focusing our attention" in a world of distraction "and directing it toward God" (Cutsinger 1998, 124) hence a "direct aid to spirituality" (Schuon 1982a, 62).

This is so important a part of human life that each of the great revelations "created and formalized its sacred art before elaborating its theologies and philosophies." Sacred art is as necessary to spiritual accomplishment as it is because "man lives in the world of forms" and therefore "to reach the formless, man has need of forms." "Form is the reality of an object on the material level of existence. But it is also, as the reflection of an archetypal reality, the gate which opens inwardly and 'upwardly' unto the formless Essence" (Nasr 2007, 204, 210).

Art, as with ritual, is a "means of exercising the mind and sharpening the perceptions, of providing for each of the senses its appropriate 'supports,' and as a help for canalizing attention towards the point desired...the acquisition of the one essential faculty of direct, undistracted intellectual intuition of the Truth" (Pallis 1949, 351-352).

The action of this reminding and support, the 'how' of sacred art, is shock, an echo of the Formalists' ostrananie or defamiliarization. As Coomaraswamy explained in his essay 'Samvega: Aesthetic Shock:'

The Pali word samvega is often used to denote the shock or wonder that may be felt when the perception of a work of art becomes a serious experience.... [The word] refers to the experience that may be felt in the presence of a work of art, when we are struck by it, as a horse might be struck by a whip. It is, however, assumed that like the good horse we are more or less trained, and hence that more than a physical shock is involved; the blow has meaning for us, and the realization of that meaning, in which nothing of the physical sensation survives, is still part of the shock....

In the deepest experience that can be induced by a work of art (or other reminder) our very being is shaken (samvijita) to its roots....and it is for this reason that it can be described as 'dreadful,' even though we could not wish to avoid it.... That cannot have been an 'aesthetic' emotion, such as could have been felt in the presence of some insignificant work of art, but represents the shock of conviction that only an intellectual art can deliver, the body-blow that is delivered by any perfect and therefore convincing statement of truth (Coomaraswamy 2004, 196-197).

Unlike the Russian Formalists, whose defamiliarizing aim was to cause a reawakening or freshness of experience from the slumber of unconscious life inside conventional thinking, the artistic samvega or shock according to the Perennialists has the specific goal of recalling the audience from sensual distraction to spiritual focus and acting as a support to their contemplation of what is real and true.

Un-Natural or Super-Natural Art: Imitating the Exteriorizing 'Methods of Operation'

The appearance of this art is not an imitation of God's creation, which is to say, depiction of the natural world. Perennialists after Coomaraswamy[4] uniformly cite Aquinas' explanation of this in his Summa Theologica: "Art is the imitation of Nature in her manner of operation: Art is the principle of manufacture" (Q. 117, a. I). "The work of the creator [artist], whenever he looks to the unchangeable and fashions the form and nature of his work after an unchangeable pattern, must necessarily be made fair and perfect, but when he looks to the created order only, and uses a created pattern, it is not fair or perfect" (Timaeus 28A, B, cited by Nasr 2007, 212).

The doctrine common to traditional civilizations prescribes that sacred art must imitate the Divine Art, but it must be clearly understood that this in no way implies that the complete Divine creation, the world such as we see it, should be copies, for such would be pure pretension; a literal 'naturalism' is foreign to sacred art. What must be copied is the way in which the divine Spirit works (cf. St Thomas Aquinas, ST 1.117.1). Its laws must be transposed into the restricted domain in which man works as man, that is to say, into artisanship (Burckhardt 1976, 10).

The artist "therefore imitates nature not in its external forms but in its manner of operation as asserted so categorically by St. Thomas Aquinas [who] insists that the artist must not imitate nature but must be accomplished in 'imitating nature in her manner of operation'" (Nasr 2007, 206). Schuon described naturalist art which imitates God's creation in nature by faithful depiction of it, consequently, as "clearly luciferian." "Man must imitate the creative act, not the thing created," Aquinas' "manner of operation" rather than God's operation manifested in created things in order to produce 'creations'

which are not would-be duplications of those of God, but rather a reflection of them according to a real analogy, revealing the transcendental aspect of things; and this revelation is the only sufficient reason of art, apart from any practical uses such and such objects may serve.

There is here a metaphysical inversion of relation [the inverse analogy connecting the principial and manifested orders in consequence of which the highest realities are manifested in their remotest reflections[5]]: for God, His creature is a reflection or an 'exteriorized' aspect of Himself; for the artist, on the contrary, the work is a reflection of an inner reality of which he himself is only an outward aspect; God creates His own image, while man, so to speak, fashions his own essence, at least symbolically. On the principial plane, the inner manifests the outer, but on the manifested plane, the outer fashions the inner (Schuon 1953, 81, 96).

The traditional artist, then, in imitation of God's "exteriorizing" His interior Logos in the manifested space-time plane, that is, nature, instead of depicting imitations of nature in his craft, submits to creating within the revealed forms of his craft, which forms qua intellections correspond to his inner essence or logos.[6] The work produced in imitation of God's "manner of operation" then resembles the symbolic or iconographic quality of everything existent in being a transparency whose allegorical and anagogical content within its traditional forms is relatively easy to access and a consequent support and edifying shock-reminder to man on his spiritual journey.

The spiritual function of art is that "it exteriorizes truths and beauties in view of our interiorization... or simply, so that the human soul might, through given phenomena, make contact with the heavenly archetypes, and thereby with its own archetype" (Schuon 1995a, 45-46).

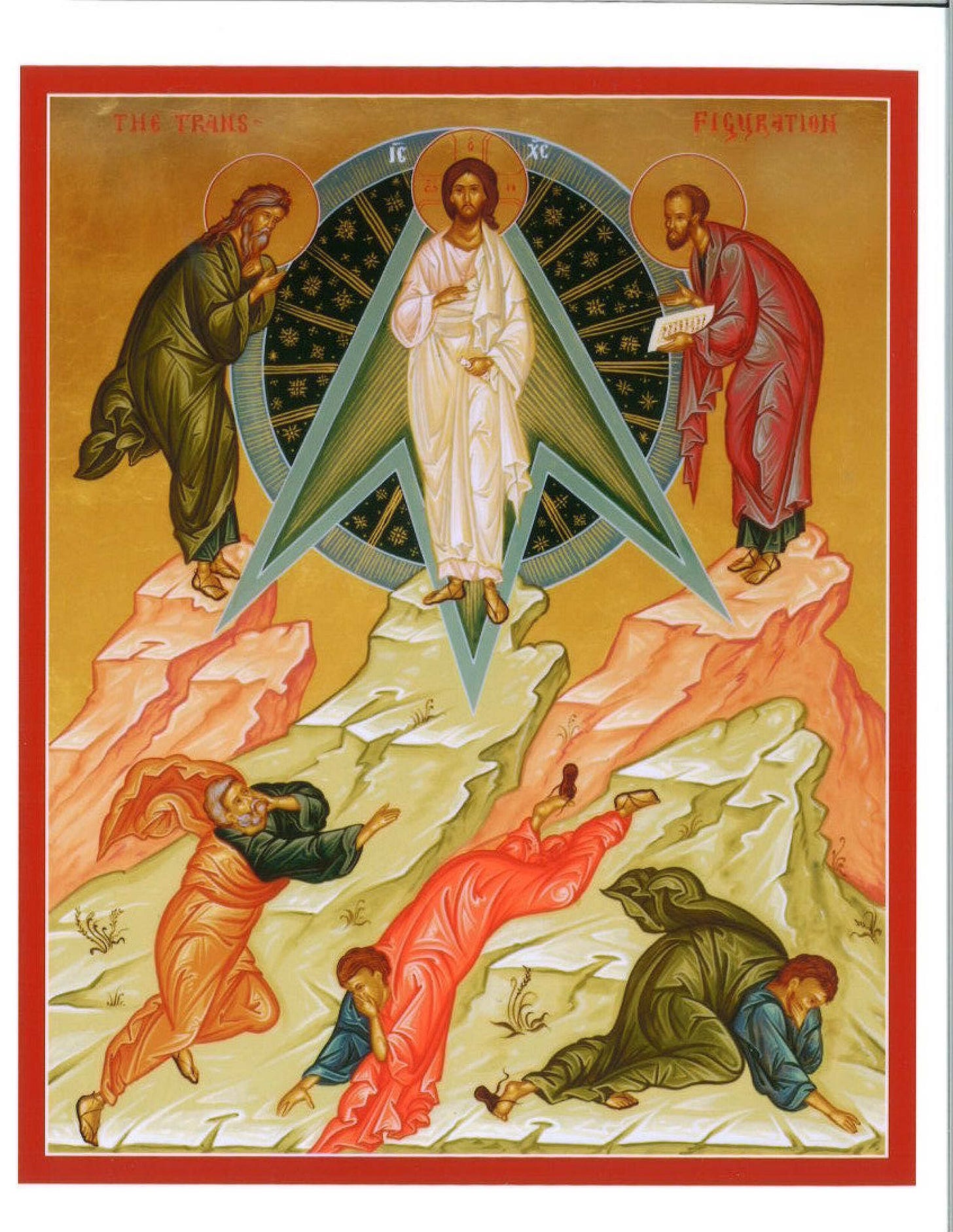

From this perspective, Raphael’s ‘Transfiguration of Christ’ is by definition profane art with a religious subject rather than sacred art. It is a naturalist depiction of the scenes in question from scripture with the illusion of three dimensionality because of geometric perspective. Contrast it with the traditional icon of the Transfiguration used in Orthodox Christian worship:

I will not list here the differences between Raphael’s work and the icon above, almost all of which are obvious on first viewing. For an excellent overview, though, of the gulf separating art that imitates nature, “illusionism,” versus the Creator’s “method of operation,” Medieval “realism,” I recommend Hilary White’s explanation of the difference between Catholic and Orthodox depictions of the Dormition of the Mother of God (‘The Assumption’ in the West) and especially her ‘Lies the Renaissance Told You,’ for her overview of when and how, in her terminology, sacred art became secular.

I will note, though, that the ring around Christ in the Transfiguration icon, the so-called mandorla or almond, is traditionally the same shape as the Ichthys fish, the intersection of two circles, albeit on its side. The symbolism of this intersection of heaven and earth, the God-Man, plays an important part in understanding Rowling’s favorite painting, Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus, and Rowling’s use of it as the mother-of-pearl fish pendant in Running Grave.

The mandorla is restricted in Orthodox iconography to icons involving Christ and His Mother and are most evident in the icons of the Resurrection, the Transfiguration (which is Christ’s preparatory revelation to His Apostles of His divinity before His Crucifixion), and the Dormition of the Mother of God.

Raphael’s beautiful painting of the Transfiguration has a covert message imbedded in its romantic and emotive naturalist depiction of historical events. If Wikipedia is to be believed, it was the most famous and admired painting in the Western world until the early 20th Century when Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and Last Supper supplanted it (fun fact: Napoleon made its transfer to the Louvre one of the conditions of his peace treaty with the Vatican States after he conquered Italy).

But in that representation there is no transcendence of the world or touching on eternity; beyond its use of traditional colors for virtues and ideas, it neglects the symbolism that makes painting iconographic, a transparency of verities outside time and space, that are such an important part of receptivity to graces from the spiritual realm above the psychic. The painting played an important part in my life as a thinking person, for which I am grateful, but ironically it was its role in turning me toward an appreciation of sacred art that makes having sat before it such a benchmark moment for me.

Sacred Art and J. K. Rowling

It is worth pausing after this relatively metaphysical discussion and personal conclusion to touch base with its relevance to J. K. Rowling and the interpretation of her work (what you’re here for!). Perennialist ideas about art and sacred art, it turns out, may clarify the meaning of otherwise mysterious comments Rowling has made in interviews and throw some light on the right way to read her work.

For example, Rowling pushed back in her 2008 interview with Juan Cruz for El Pais on the suggestion that she was only writing wish-fulfillment fantasy, which is to say from her psychological needs, rather than from a greater purpose:

Q: Literature saves people, or helps to save them. How did writing affect you?

A: Let me tell you one thing. Simply the fact of writing the first book saved my life. I’m always told that the world I created is unreal; it was that which allowed me to escape. Yes, it’s true; it’s unreal up to a point. But not because my world was magical but because all writers evade themselves. Additionally, I did not write only to escape but because I searched to understand ideas which concerned me. Ideas such as love, loss, separation, death… (Cruz)

In conventional use, Rowling’s use of the word ‘ideas’ here can be read simply as ‘notions’ or, more elevated, as ‘themes.’ ‘Ideas,’ though have a specifically Platonic meaning as well, that is, they are the archetypes or universal forms of which existent, ephemeral, “sub-lunary” forms of things in the world of becoming rather than being are only correspondent shadows. As Seyyed Nasr noted:

The form which is wed with matter [as God creates according to hylomorphic understanding] and the form which is the “idea” in the mind of the artist are from the same origin and of the same nature except on different levels of existence. The Greek eidos expresses this doctrine of correspondence perfectly since it means at once form and idea whose origin is ultimately the Logos (Nasr 2007, 213).

Rowling’s insistence that she was writing “not only to escape” her unpleasant circumstances as a single mother on the dole but also because she “searched to understand ideas which concerned me” suggests at least that her self-image as a writer is if not Perennialist per se at least not contrary to the workings of a sacred artist working with revealed traditional forms.

In her last answer at the same interview, she makes a distinction between writing inspired by psychological need or unresolved issues, the Lake, and the deliberate Shed artistry of “creating a world:”

Q: Maybe writing is some kind of Resurrection Stone.

A: Yes, of course, but I think you realize that once you’re writing to make a dream come true. If it’s just like that then, for me, writing loses its worth. Describing your fantasy is not the same as creating a world (Cruz).

This interview was translated for publication in El Pais from a conversation in English into Spanish; the version available to English speakers, consequently, is not the original but a re-translation back into English.[7] This parting answer, Rowling’s last words as it were, perhaps because of their obscurity were not included in the Cruz article but survive because they were posted at the magazine’s website at the time as “extras.”

What she meant may be clarified, again, with reference to the Perennialist ideas of art. The author made a distinction between “describing your fantasy,” i.e., writing inspired by personal psychological reasons, and “creating a world,” what she did in her Wizarding World, a magical reality just out of sight of Muggle existence. She did not cite Aquinas’ dictum about an artist imitating the divine “method of operation” in creating the natural world in an imaginative echo or sub-creation, but her comment to Cruz echoed it.

Schuon described this “imitation” explicitly as “exteriorization,” the creation of transparencies of spiritual realities within sacred forms in art, what in story, as discussed here, are symbolic representations of supra-natural referents or allegories of the soul’s journey to spiritual knowledge. Rowling is reticent to discuss her work in light of her Christian faith and the journalists who have interviewed her have rarely pressed her on the subject. When she has been given a direct question, however, she has admitted allegorical and symbolic Christian content.

She said for example that she intentionally gave Harry Potter “messianic traits” (deRek), that she had always thought the Christian symbolism of her Hogwarts stories was “obvious” (Adler), and, while denying that “Dumbledore was Jesus” as Aslan was in Lewis’ Narniad (Grossman 2005), she said in an interview with David Radcliffe as a DVD extra that she thought of the Headmaster as a “John the Baptist figure” in relation to Harry as Christ (Radcliffe). When Grossman described the Potter books as secular, she corrected him, politely but firmly (from Grossman’s unpublished transcript notes):

Q: whereas your books are quite thoroughly secular – there’s no God at all in Harry Potter. A: Ummm [choosing words very carefully] I don’t think they’re that secular. But. Obviously Dumbledore is not Jesus. And, I am certainly not working to any religious agenda. I think that the wizarding world is an interesting view of our world, in a sort of distorted mirror. so that it’s as religious or irreligious as our world is…. I didn’t give [the boy who asked me if wizards believed in God] a very full answer, because it was going to reveal things that I didn’t particularly want to reveal, and I suppose I can’t really give you a very full answer until book 7 is out there. but [sighs] I’m trying to find ways of saying things that I –

well, well, I can certainly say, end of Phoenix, um, I think you do come really up hard against the notion of death, what does death mean. And you are given certain choices through the characters [in their reactions to the Veiled Arch in the Department of Mysteries], aren’t you? you’re given ron’s determined – and probably quite healthy, in a 15-year-old boy, -- not interested in what’s beyond the veil, and let’s get out of here. Harry’s attraction towards it – harry’s actually quite attracted to it. right through to luna’s belief that there is not only something beyond the veil, but that she can hear them talking beyond the veil. and that’s, that’s something that will be resolved as the books go on (Grossman 2017).

Deathly Hallows, the “book 7” she mentioned, has the Into the Forest scene and King’s Cross dialogue she has said are “the keys” that unlock the meaning of the story, things she did “not particularly want to reveal” to a reporter at the publication of book six in the series, Half Blood Prince. She denied the books are secular, though, distanced herself from openly evangelical allegories, and pointed at the same time to the soul’s evident survival of death in Order of the Phoenix.

This was the “explicit” answer she alluded to in her 2007 conversation with Amini about the psychological or other-worldly interpretation “debate” she wanted to foster about the reality of the King’s Cross experience Harry has. Here it was her embedded answer to the secular or spiritual question Grossman posed.

Her comment to Amini, too, about the controversy about magic among Christians tips her hand, too.

There was a Christian commentator who said, which I thought was very interesting, that Harry Potter had been the Christian church’s biggest missed opportunity. And I thought, there’s someone who actually has their eyes open. I think he said it before the publication of the seventh book, and with the publication of the seventh book I think that clarified a lot of people’s view on where I was standing (Amini).

One of the “people” she may have been referring to here may have been, oddly enough, in addition to Christian “fundamentalists,” Lev Grossman, public atheist, who two years after his interview with Rowling wrote an article for TIME in the run-up to the publication of Deathly Hallows titled, ‘Who Dies in Harry Potter 7? God’ (Grossman 2007).

That Rowling might be writing what the Perennialists would call “non-liturgical sacred art” or something akin to it while still not “writing to a religious agenda” is not hard to imagine. To explore that possibility from a Perennialist perspective requires exposition of their understanding of specifically literary arts among all others and of the possibility of writing traditional story in anti-traditional times. Each of the five chapters in my PhD thesis, a Perennialist reading of Rowling, was introduced, consequently, with explanation of the Traditionalist view on the specific subject, e.g., symbolism or alchemy, in light of their definitions of sacred art.

So What?

I have been reading and writing about Rowling-Galbraith for twenty-five years. 2025 is my silver anniversary, believe it or not, as a leader in the niche field of Rowling Studies. I’m delighted both that my work has stood up to the test of time and by the number of wonderful friends I’ve made along the way.

I want to note here, though, that all of my signal contributions to understanding Rowling’s work spring from my Perennialist understanding. I don’t think it’s self-importance or self-promotion to point out that my five insights to grasping Rowling’s Shed artistry — her signature use of literary alchemy, depictive psychology or psychomachia, mythological templates, ring composition, and Christian symbolism — were ground-breaking discoveries that inform almost all serious writing today about Harry Potter, Cormoran Strike, or The Christmas Pig and other stand-alone stories. As a one time writer at Hogwarts Professor wrote to me, “No one has contributed to this field what you have.”

I started writing about Harry Potter because I wanted to know why readers, to include myself and my children, loved those stories the way that we did and do. My conclusion in essence, what I tagged the ‘Eliade Thesis,’ was that the love springs from her doing in story what her readers around the world most want from story; per Eliade, in a profane culture, stories serve a mythic or religious function; they deliver spiritual oxygen to God-deprived people longing self-transcending experience. Rowling-Galbraith is the giant among writers today despite her being an undeniably postmodern artist writing for a postmodern audience because she uses traditional tools that are all about the representation of the soul’s perfection in the spirit and transcending death in love.

I recognized those tools and Rowling’s consequent principal aim as a writer deploying them because of my familiarity with Perennialist reading of literature as non-liturgical sacred art and my ability to argue effect to cause, per Eliade. I was taught to read at the four levels of reading, the Pardes or ‘Garden’ method, per Rabbinic tradition, Patristic hermeneutics, Aquinas, Dante, and Flannery O’Connor, in which the surface and moral levels were the surface story above the much more important though covert allegorical and anagogical depths. I wrote Harry Potter’s Bookshelf, nominally a survey of Rowling’s favorite genres and writers, to introduce reading for the sublime content rather than being consumed by the surface story. This is the book Nick Jeffery says taught him not only what to read but also how to read.

I believe that this reading at depth is the right way to read the work of J. K. Rowling, the best way. There are other ways certainly, most notably the fandom obsessions both with representations in film (the ultimate medium for profane art or illusionism, whence its being the defining ‘art’ of our secularist age and consumer culture) and with possible outcomes of series in progress as well as the academic approach that focuses on themes and spot-the-source intertextuality.

Those ways are fun, for the most part, and interesting if you’re into the writing of readers who think as a rule along the lines of accepted university English department protocols and guide rails. Note, though, that neither of those approaches yields anything akin to, say, literary alchemy, psychomachia, or ring composition in getting at what the writer is about and why readers respond to their work as they do. When Rowling’s work was being dismissed as trash “unworthy of adult attention” by the literati and academics universally and as “the gateway to the occult” by Culture Warriors, only a Perennialist reading of her work was able to turn that tide. Now even third tier Shakespeare scholars on tenure tracks tenuously are on Team Rowling and Christian churches celebrate Harry Potter as edifying reading for young believers.

I have recently been criticized because I have discussed the most neglected and mysterious of Rowling’s Golden Threads, namely ‘The Lost Child,’ and floated the hypothesis that its origin in Rowling’s Lake was an induced abortion conceived with her long-time boyfriend, Michael Corleone. That criticism was expected because such a hypothesis is necessarily speculative, though text based, because the subject of foeticide is a hair-trigger issue for most people, and because those who have something like a reverence relationship with The Presence naturally must rise up in her defense on social media.

I asked during my Kanreki conversations with Nick Jeffery about these subjects for listeners to share their Lost Child Golden Thread alternative hypotheses to my lay out of the most obvious and controversial explanation. We were delighted by the three alternatives we were sent and look forward to a continuing discussion at Hogwarts Professor about this Golden Thread going forward.

What I wanted to see in response, however, but didn’t request was for someone, anyone, to ask, “Hey, John, really? What does this have to do with Perennialism, literature as sacred art, and reading Rowling’s work for its allegorical and sublime meaning? Where’s Eliade in a possible not probable trip by a much younger Rowling to the abortuary?”

That’s the question I had to answer to my own satisfaction before I ‘went there’ on Rowling’s birthday this July. Perennialists without exception in my reading have nothing but disdain for criticism or interpretation based on biography. The answer, one that made the use of Perennialist methodology for my thesis possible, came from the idea of intention.

The obvious, logical, and perhaps fairest place to begin looking for the most appropriate critical approach to an author’s work or combination of methods is, if available, what the writer herself claims was her ambition in writing and then choosing the tool or tool sets most fit to gauging whether she succeeded or failed in that effort. This is in concordance with A. K. Coomaraswamy’s dictum that “The only possible literary criticism of an already existing or extant work is one in terms of the ratio of intention and result:”

“The artist’s intention is (artifex intendit) to give his work the best possible arrangement, not indefinitely, but with respect to a given end – if the agent were not determinate to some given effect, it would not do one thing rather than another” (Summa Theologia, I.91.3 and II-I.I.2) To say that the author does not know what it is he wants to do “until he has finally succeeded in doing what he wants to do” (W. F. Tomlin in Purpose, XI, 1939, p. 46) is an ahetuvada [assertion that all inferred knowledge is conditional and to be doubted] that would stultify all rational effort and that could only be justified by a purely mechanical theory of inspiration or automatism that excludes the possibility of intelligent co-operation on the author’s part. So far from this, it is, as Aristotle says, the end (telos) that in all making determines the procedure (Physics, II.2.194ab; II.9.22a). (Coomaraswamy 1944 [1977], 274)

John Updike asserted much the same thing, albeit on the basis of simple fairness and objectivity. His first principle in accessing the worth of any writer’s work in a book review was “Try to understand what the author wished to do, and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt” (Updike 1975, xvi).

Rowling has never explicitly stated what her intention as a writer was or has become through the years. The closest she has come was in 2019, again in 2024, and in recent tweets when she discussed at some length, first in a BBC interview and then on her website, how it is she writes, from the source of her inspiration to her method of transforming those received ideas into a completed story.

In an appearance on the 2019 BBC4 ‘Museum of Curiosity’ Christmas program recorded on 8 June of that year, Rowling discussed her creative process at some length for the first time. She described it as a combination of inspiration and perspiration,[8] a traveling back and forth between her personal “lake and shed.”

Readers of this Substack don’t need a review of Rowling’s Lake and Shed metaphor for her writing process (newcomers should listen to the introductory piece to our Kanreki series for that). Rowling’s process is not her intention as a writer per se; the traditional tools she uses in her Shed reflect those transformative aims. Her method, however, is essential for understanding what is the primary challenge she faces in realizing that intention.

The challenge, in brief, is her working with the material of her unconscious mind or super conscious “muse” to create a story with universal meaning and power rather than just one that is satisfying on an individual and psychological level. We know, in large part at least, the essential artistry of the Potter novels from the tools used to give it its shape and symbolic form and content; we still do not know what inspired them and the craft necessary to turn that inspiration into the wonder-full and epic Hogwarts Saga and its subcreated universe, the Wizarding World.

Whence our exploration of the Golden Threads in her work and our focus on the Lost Child thread which is nigh on ubiquitous and without obvious correspondent in her life.

Conclusion: The Hallmarked Man

Nick and I have been talking for a fortnight about how we’re going to read Strike8 here at Hogwarts Professor. Our most recent discussion was playing with the idea of looking at Hallmarked Man using the Shed tools and Lake lenses that we are the only Rowling Readers proficient in: the five tools mentioned above, the twelve Golden Threads, the seven periods of Rowling’s life to include her key relationships and core beliefs.

That reflection on the mythology, soul-spirit allegory, alchemy, ring writing, and Christian symbolism in the latest Strike-Ellacott story with its Lake back-drop will necessarily lean into it as a piece of non-liturgical sacred art or edifying, transformative myth-making. And the inevitable deep-read as a chiastic structure and of each of its multi-chapter parts as a possible ring as well, not to mention of its predicted correspondences in the Tetractys pyramid and with Casual Vacancy? We’ll ‘go there’ as well.

Thank you in advance if you choose to join us for that look into Rowling-Galbraith’s greater artistry and more sublime meanings, and, as always, for your support!

[1] The aesthetic being a “literally, ‘theory of sense-perception and emotional reactions,’ a conception and term that have come into use only within the last two hundred years of humanism” (Coomaraswamy 1956, 110).

[2] This is the title of a collection of essays by Perennialist William Stoddart, one that points to the ends not only of sacred art but to the self-understanding of the Perennialist school in general, a “voice crying in out the wilderness” of modernity.

[3] He quotes Plato in this regard: “Now since the contemplation and understanding of [sacred art] is to serve the needs of the soul, that is to say in Plato’s own words, to attune our own distorted modes of thought to cosmic harmonies, ‘so that by an assimilation of the knower to the to-be-known, the archetypal nature, and coming to be in that likeness, we may attain at last to a part in that ‘life’s best’ that has been appointed by the Gods to man for this time being and hereafter’” (Coomaraswamy 1956, 10; citing Plato’s Timaeus 90d).

[4] It is the epigraph heading Coomaraswamy's 1940 essay 'The Nature of Medieval Art' (Coomaraswamy 1956, 110).

[5] Idem, 81. Schuon there referred the reader to Guenon’s Man and His Becoming according to the Vedanta “for the metaphysical theory of the inverse analogy.” “Analogy is necessarily applied in an inverse sense… and just as the image of an object is inverted relative to that object, that which is first or greatest in the principial order, is, apparently at any rate, last and smallest in the order of manifestation. To make a comparison with mathematics by way of clarification, it is thus that the geometric point is quantitatively nil and does not occupy any space, though it is the principle by which space in its entirety is produced, since space is but the development of its intrinsic virtualities. Similarly, though arithmetical unity is the smallest of numbers if one regards it as situated in the midst of their multiplicity, yet in principle it is the greatest, since it virtually contains them all and produces the whole series simply by the indefinite repetition of self” (Guenon 1981, 41-42), This “metaphysical theory of inverse analogy” finds expression in the English High Fantasy tradition after Coleridge in the hidden “inside greater than the outside.”

[6] Schuon argued that “a sufficient reason for all traditional art, no matter what kind, is the fact that in a certain sense the work is greater than the artist himself and brings back the latter, through the mystery of artistic creation, to the proximity of his own Divine Essence” (Schuon 1953, 96-97). Sacred art is, in other words, at least as much about the sanctification of the artist as it is producing salutary work.

[7] The translation from the Spanish, according to Patricio Tarantino in Buenos Aries, the editor of ‘The Rowling Library’ and speaker of Spanish, is accurate, however opaque it may seem (Tarantino, private correspondence).

[8] “Moments of pure inspiration are glorious, but most of a writer’s life is, to adapt the old cliché, about perspiration rather than inspiration. Sometimes you have to write even when the muse isn’t cooperating” (Rowling 2019a).

This is a lot. I’m scratching my head, and intrigued to read this multiple times. There is a lot here that will help me understand your writings, and many things that certainly illuminate Rowling’s words, and eventually both, and fiction, and art. My own list of “golden threads” includes her exploration of what it means to be an artist; what is the connection between creation as an artist, a parent, and diving creation; how our own encounters with art impact us; and what is the value of divine inspiration.