Running Grave, Part Six: A Ring Reading

The Novel's First Turtleback Line is a 'Wow!' and the Interior Ring has a Surprise Inside

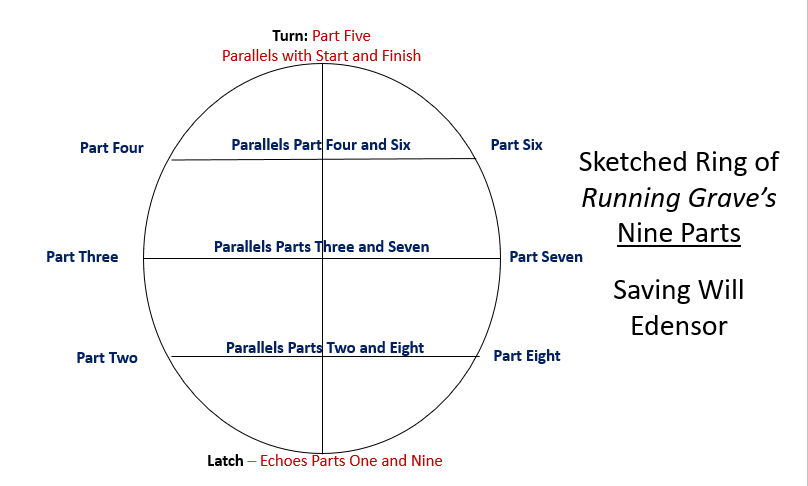

Yesterday’s ring reading of Part Five parsed the central Part of the nine Part Running Grave as its own distinct ring with latch, turn, and turtle-back parallels but also included some discussion of the novel axis, the connections between Part Five as the book’s turn and its relations to the beginning and end of the story. [I’m going to assume that the important links here are to Part One rather than the Prologue and to Part Nine instead of the Epilogue, though the latch of Prologue and Epilogue, the throat-clearing introductory material and the tying up of loose ends, will almost certainly be something to review as well.] The turn in Part Five, chapter 70 and chapters 71-72, reflected both the latch of this central Part and the ‘meaning in the middle’ of Part One.

Part Six is the first of Running Grave’s Parts that should, if the novel is a ring as the premise of this series holds, connect across the axis with parallels or inverse reflections with Part Four. Before I break down the twelve chapters of Part Six in search of its ring structure, let’s check to see if the series premise passes its second test. Does Part Six echo Part Four, and, if so, how?

Part Four is a mind-blowing piece, of course, memorable mostly for the death of Charlotte Campbell-Ross by suicide. Chapter Six is at least its equal for drama and depth of feeling with Robin’s torture session in the UHC box and her by-the-skin-of-her-teeth escape from Chapman Farm. The parallels, I think, are inverse, which is to say, in being contraries or opposites, with one major exception.

In Part Four, Charlotte pursues Strike and he ignores her repeated calls for help (and threats, yes, which are also a sort of call for help). He frets and worries about how she might hurt him, though. She winds up in a box, alas, after committing suicide. She meets with Strike in the end as the ghost who talks, those-who-never-leave-us, at the Aylmerton church, testimony to their profound psychic connection, and he leaves there with a new understanding of himself, his history with Leda and Charlotte, and his relationship with Robin.

In Part Six, Strike pursues Robin and drops everything when she does not call him (leave a note in the plastic rock). She is put in a box by the UHC Principals after agreeing that she accepts her need for penance, which is to say, punishment, rises from this imprisonment, and has a psychic connection with Strike — the sure realization that he is waiting for her outside the perimeter — and escapes the Farm and the mind-control grip of the UHC. She and Strike sleep together as Platonic lovers, partners and friends, she being unaware either of his new resolve to be open with her about his feelings or of the Bijou affair’s status.

Charlotte dies because Strike will not save her; Robin lives because Strike saves her. Both women have an out-of-body connection with him: Charlotte in the church post mortem, Robin in the farmhouse attic, Jacob’s nursery, after her being buried alive or its claustrophobic equivalent in a box.

There are other parallels across the axis.

Taio Wace has Robin in a Retreat Room against her will in Part Four’s chapter 54; they’re on their way to do the deed there the night she escapes in Part Six.

Daiyu “manifests” at Robin’s Revelation session and almost dumps her into the pentagram pool of dark water in Part Four’s chapter 53; the big moment of the Drowned Prophet’s Manifestation in Part Six — as an “eyeless child in a white dress” inside a pool water “bell jar”? — climaxes with Robin being drowned in the pool (remember, folks, the headline Robin reads in Jacob’s lair: “SOCIALITE DIED IN BATH”).

Jordan Reaney tells Strike his history at the Aylmerton Commune in chapter 56, Part Four; Shanker learns that the call to Reaney that moved him to attempt suicide was from Aylmerton or Comer in Part Six, chapter 85.

Robin is interrogated in Mazu’s office in Part Four, chapter 57, and learns that they are keeping her mail from her; Robin is grilled by Jonathan Wace in Mazu’s presence in Part Six, chapter 82, about her conversation with Will, a beat-down largely turning on Will’s new desire to communicate with his “flesh object” Sally (Robin’s defense is that she told him she thought mail was being kept from them).

Robin overhears the Principal’s discussing Jacob’s fate in the same Part Four chapter and learns that Becca is somehow related to him; in Part Six, chapter 86, Emily tells her that Jacob is the Pirbright sisters’ half-brother.

I’m certain that there are more 4-to-6 connections that my first overview of the ring charts I’ve drawn for these two Running Grave Parts has missed. The big take-away, regardless, is ‘Charlotte Dies: Robin Lives,’ the parallels of bath, box, and psychic connection with Strike, and the transformation in Strike each of these women’s escapes catalyzes. Both women escape their private hells, escapes accomplished on their own, for better or worse, and meet with Strike to share their thoughts. Great stuff for ring readers, methinks.

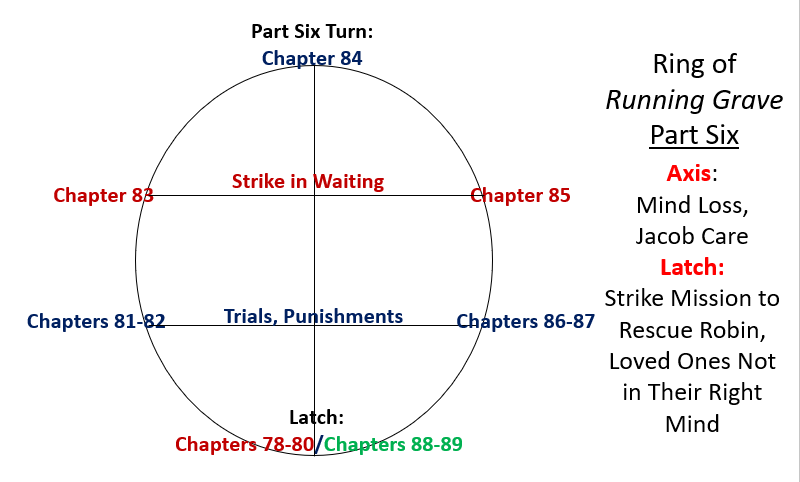

On to the parsing of Part Six’ interior ring.

The Latch: There’s no obvious link between the opening three chapters of Part Six and the close’s two chapters. In the first Strike is consumed with Uncle Ted business, the disappearance of the Torment Town Pinterest page, meeting QC Humbold, and finding Carrie Woods, aka Cherrie Gittins. His longest piece of work on the case is his trying to decipher the garbled tape of Farah Navabi’s interview with Kevin Pirbright. The end, of course, is Robin and Strike’s night at the Bramble Guest House, Fellbrigg Lodge, after her escape from the Wace brothers. They exchange news, carefully editing out the parts they don’t think the other needs to hear just now, and Robin talks with the Norfolk Police in the hope of rescuing Jacob (good luck with that…). That’s not a Venn Diagram with a lot of intersecting material, right?

The first correspondence I see is that Strike learns from Dev Shah at the very end of the opening chapters that the plastic rock has disappeared from the blind-spot in the Chapman Farm perimeter. Strike immediately abandons his drive to Thornbury on his way to see Gittins in order to hightail it to Norfolk and rescue Robin. The closing chapters begin with Strike and Robin in his car after her successful escape, in which he played an essential role (pulling her over the wall, hitting Taio with the wire cutters, etc.). The end of the beginning and the beginning of the end connect neatly.

A better connection, though, is that the beginning and end of Part Six are about mentally damaged people that Strike loves but about whom he has little idea with respect to helping them.

On the front side, Uncle Ted’s dementia is on a downhill, accelerating course, and, besides getting him a doctor’s appointment in London to make that decline an official diagnosis, he, Lucy and Greg argue about the best ways to care for him (Greg and Lucy’s marriage looks like it also is on the edge of a cliff).

On the back end, Robin is not well. Everyone is thrilled that she is free at last and safe, but she really is messed up from her time in the box, the threat of rape in the Retreat Room, and because of the months of anxiety inevitable with living undercover among fanatics. Prudence or a therapist with similar qualifications will need to be her first stop on her return to London.

That’s probably good enough to say, “It’s a latch!',” but I’m going to stretch for one more connection: Kevin Pirbright.

In chapter 89, Robin shares her conviction that Wace killed Pirbright.

“At least we know now.”

“Know what?”

“The lengths they’re prepared to go. I can imagine Wace crying as he pressed the trigger of a gun. ‘I wish I didn’t have to do this’.”

“You think they killed Kevin Pirbright?”

“I do, yes.” (635)

This is the weirdest kind of pillow talk, right? Robin has done everything she can to rescue Jacob Pirbright-Wace since her escape but her final take-away before sleeping is about the murder of Kevin Pirbright. I think that’s a Rowling marker for us to stop and think, at least if we’re in the business of charting the structure of her work (which we are). This Pirbright mention highlights or at least points to the Kevin Pirbright tape in Part Six’ opening’s central chapter.

Time-out for a closer look at that tape.

Here is my translated version of the almost unintelligible transcript we’re given of the Navabi-Pirbright interview, a mess that almost certainly contains an essential clue if only because of its being so hard to read. (The brief highlighted portion is the exchange that Strike rewound so he could hear it again, so perhaps that is the key point — or the key point is what is missed or not said in it?)

Navabi (N): I’ve always been interested in the UHC

Pirbright (P): — won’t do it — sisters — still in B(irmingham?) — maybe leave one day

[Welshmen!]

P: — evil people. Evil.

N: How were they evil?

P: — mean, cruel — hypocritical — I’m writing a book

N: Oh, wow, that’s great

(Indecipherable fifty minutes)

P: — and she drowned — said she drowned

N: (loudly) — talking about Daiyu — ?

P: — funny things happening — things I keep — remembering — four of them —

N: (loudly) Four? Did you say four —?

P: — more than just three [‘Shree’] — nice to kids, and she — Becca made Emily lie — invisible — bullshit —

N: (loudly) Becca made Emily lie, did you say?

P: — drugged — she was allowed out — she could get things — smuggle it in — led her away with stu(dents) [or ‘let her have her way with students’?]— didn’t care about her real — she had chocolate once and I stole some — bully, though —

N: (loudly) — Who was a bully?

P: — make allowances — going to talk to her — [she?] is going to meet me

N: (loudly) Is someone from the church going to meet you, Kev?

P: — and answer for it — Dopey — part of —

N: (insistent) Are you going to meet someone from —?

P: — she had a hard time — in [or ‘and’] the pigs —

N: (exasperated) Forget the pigs —

[“Let him talk about the fucking pigs,” growled Strike at the recorder.]

P: — he liked pigs — knew what to do — because why — and I was in the woods — and Becca — told me off because — Wace’s daughter — mustn’t snitch

N: — Daiyu in the woods?

P: Don’t know — was she — think there was a plot — in it together — always together — if I’m right — [contri]bution — [and/in] woods — wasn’t a — gale blowing on — fire but too wet — weird and I — threatened me — and out of the — thought it was for punishment — Becca told me — sorry, got to (592-593)

Forgive me for thinking that the tale of Daiyu’s ‘death,’ not by drowning, is in this bowl of pottage. Using what Emily told Robin in their hurried last truth-telling exchange in Jacob’s attic,* I think we can piece together what drunk Kevin was trying to share with Farah about that fateful day.

*When Robin says, “You owe me” to Emily, I thought of Harry Potter and Peter Pettigrew in the Malfoy Manor basement. I won’t be surprised if Emily commits suicide — death by her own hand, that hand being directed by the Waces — consequent to Robin’s escape. Or will she just be put back in the dreaded box, given that the police have to be expected soon, and buried in the vegetable garden, where overturned earth won’t draw attention. Does Emily’s aversions to the Farm’s vegetables spring from what she knows is already buried there?

Emily in chapter 86 tells Robin that she told Kevin years later about what happened the night Daiyu disappeared, either at the Comer beach or elsewhere. His sister is his main source of information about that part of the story and there are some clear points of correspondence in their recollections.

“[Daiyu] went into the woods, and into barns. I asked her and she said she was doing magic with other people who were pure spirit.”

Kevin talks repeatedly on the tape about being “in the woods” and Farah asks explicitly about “Daiyu in the woods,” perhaps to clarify something he said about that. The “magic with other people” in the woods points to that circular clearing with the stakes and “charred rope” that Robin stumbled into twice. Were people tied in place there for some kind of ceremony or sacrifice — or was it pigs? Mazu is the likely candidate for the “pure spirit” person.

“Sometimes she had sweets and little toys. She wouldn’t tell us where she’d got them, but she’d show us. She wasn’t what they say she was. She was spoiled. Mean.”

Kevin uses the word “mean,” but it seems he is talking about the UHC in general? When he talks about a girl or woman who was “was allowed out” and who “could get things, smuggle it in,” he mentions this specifically with respect to candy: “She had chocolate once and I stole some… a bully, though.”

The “bully” piece there matches with Daiyu being “mean,” but it doesn’t make sense. Daiyu was a young girl who couldn’t have been “allowed out” in the sense of going into town and buying candy. That has to be Cherie Gittins, no? Daiyu would be getting candy from Cherie who bought or nicked it when “allowed out” to beg for money or sell trinkets in Norfolk.

Emily told Robin that “Daiyu told me she was going to go away with this older girl [Cherie] and live with her…. I was so jealous. We all really loved Cherie, she was like… like a real… like what they’d call a mother” (620). Kevin’s most garbled sentence suggests someone who had a special relationship with the kids, a teacher: “[They] led her away with stu(dents) [or ‘let her have her way with students’?]— didn’t care about her real —.” This could be Louise, I guess, a woman who neglected her real daughters and son, but the son in that case would be Kevin; I think he’d note that he was talking about his mother.

This person is the one, it seems, that Kevin tells Farah he is “going to meet” and who is going to “have to answer for it.” He seems especially upset about what happened to Dopey, the pig keeper, who was punished to the point of irreversible brain damage for the pigs escaping on his watch.

P: Dopey — part of —

N: (insistent) Are you going to meet someone from —?

P: — she had a hard time — in/and the pigs —

N: (exasperated) Forget the pigs —

[“Let him talk about the fucking pigs,” growled Strike at the recorder.]

P: — he liked pigs — knew what to do — because why — and I was in the woods — and Becca — told me off because — Wace’s daughter — mustn’t snitch

It sounds like Kevin saw a pig ceremony of some kind in the woods, at which Daiyu may or may not have been, but the celebrant needed help with the porkers. The pigs didn’t escape; Dopey was helping Cherie and Mazu with them in the forest circle? Perhaps Daiyu out of jealousy told people that Dopey let them escape and Kevin was told not to “snitch” because she was “Mace’s daughter”?

Brian Kennett, Sheila’s husband, we were told (137) “loved his pigs”* and had a hankering for Leda Strike (or perhaps any woman not as prone to miscarriages as Sheila — egad, was he giving her mugwort? Were they both eating it and that is what prompted his tumor?). So it was probably Brian the Hippie who was the pig handler in the forest circle.

*Re-reading chapter 17 to find Sheila’s comments about her husband and the pigs, I think I found another gaffe, this one about Mazu. Sheila reports that she helped a 14 year old named Ann deliver her baby with Dr Coates at Forgeman Farm or Aylmerton Commune, that baby being Mazu. I don’t know how many years the Kennett’s are working the land and animals there, but, after they leave for “two years… three years,” it is Mazu — as Mrs Allie Graves? — who wrote to them to call them back; “she said it was all better and they had a good new community” (138).

The Graves matriarch told Strike that Mazu was “very young” when she met Allie, but she and her husband the Colonel felt she was the person in charge (309). “She can’t have been more than sixteen, and Allie was twenty-three when he met her,” which was in 1997 or so because Mazu had baby Daiyu in 1998 (310). We learn in that chapter that Nicholas Delaunay went to school with Allie and was with him when he got into a bar fight (307-308) and that Allie had a real problem with marijuana (“the psychiatrist fella diagnosed this manic what-have-you…” “and he said Allie mustn’t smoke pot any more” 308). [For the link between marijuana, psychosis, and violence, see this report.] Sheila Kennett told Robin that Allie Graves would “smoke [pot] half the night” with Rust Anderson and “he couldn’t handle it. He went funny” (138-139).

I suspect there’s a gaffe here in Mazu’s age; she couldn’t have been much older than 13 or 14 when she had Daiyu by these dates, which would make the father, Wace or Graves, statutory rapists, there being no consent possible at that age. Of course, child molestation is a thing in Strike7, so maybe that’s not a gaffe. The marijuana bit and the anger Delaunays show after the Graves family interview about the investigation Strike is doing make them look like the black hats in Allie Graves’ ‘suicide.’]

N: — Daiyu in the woods?

P: Don’t know — was she — think there was a plot — in it together — always together — if I’m right — [contri]bution — [and/in] woods — wasn’t a — gale blowing on — fire but too wet — weird and I — threatened me — and out of the — thought it was for punishment — Becca told me

There’s somebody missing here, I think. Jaing told Robin in Part Five that there was someone at the Farm who had lived there years ago but who had come back. The only older people in Robin’s retreat group are Walter the retired professor and Marion Huxley, the fanatic. Could Marion be Cheri? A Doherty daughter? I don’t have the faintest idea who Walter could be; was there a surviving Doherty boy?

Regardless, “there was a plot” made by people who were “always together.” I translated the word-fragment “-bution” in the original into “contribution,” though I suppose it could be “retribution,” if that seems a bit of a stretch for Kevin in his condition that night. Ten again, a quick check for something else reveals that “retribution” is one of the words that Kevin Pirbright wrote on the wall of his apartment before being shot (81).

If we give “contribution” a chance, I’m wishing this could be Allie Grave, who was “always together” with his wife Mazu, daughter Daiyu, or Cherie. But of course his death precedes Daiyu’s supposed demise; she is disappeared so the Wace’s can keep the 250,000 pounds sterling she inherited. The only people who were “always together” that we know about are Emily and Becca — they are separated soon after — and perhaps Cherie and Daiyu, but who plots with a young child?

If the “contribution” is coming from Nicholas and Phillipa Delaunay as representatives of Allie Graves’ parents, Daiyu’s supposed grandparents, the “Daiyu’s posh aunt” chiasmus villain ‘murderer in the middle’ and her husband from Part Four’s interview with the Heatons, then maybe Kevin is saying those were the ones “always together” with Mace and Mazu, making a plot, the “four of them.”

But it’s almost certainly “retribution” rather than “contribution” — but retribution for what? The people in the piggie polaroids perhaps want pay-back in person but Dopey, Jordan, and Brian are dead, brain-damaged, or in jail and Cherie, if she is the girl in curls, is way off-screen, presumed dead or on the run. And from whom would they be exacting retribution? The Maces, I assume, maybe Daiyu for whatever happened in the Forest; if something went wrong in the Forest circle-ceremony, and Daiyu died, that would mean it was the Waces seeking revenge on those involved, the pig-keepers and child-minders, whom they set-up with the beach-trip and staged drowning…?

No, Daiyu was alive and going through the window the morning of her supposed drowning. Unless Cherrie put her out the window and Brian (her lover?) caught her and ‘took her out,’ as the saying goes, and the beach trip was just the way they covered their tracks. Having had their revenge on the Waces or just Daiyu in the forest, then Mazu and Papa J had their retribution on the pigs via the I Ching piggie reading?

Lotta crazy speculation there for the half-word “-bution.” Back to Kevin’s tape:

Somebody threatened the peeping-Tom out-in-the-woods child-Kevin with something hidden in the box (?) he “thought was for punishment”(?). The burned rope that Robin found (how many years later?) could be from the ceremonial or sacrificial fire they found it hard to start in the woods that night because of wind and rain.

Something tells me that the bust up in the woods leads to the Daiyu disappearance scam. Emily told Robin, “it was the night before they went to the beach. Cherie gave us all special drinks, but I didn’t like the taste. I poured mine down the sink. When everyone else was asleep, I saw Cherie helping Daiyu out of the dormitory window. I knew she didn’t want anyone to see what she’d done, so I pretended to be asleep, and she went back to bed” (620).

Robin asks the common sense question, “She pushed Daiyu out of the window and then went back to bed herself?” If Daiyu was going in the car to the beach that morning, why would Daiyu be pushed out the window by Cheri who goes back to bed rather than head out to the truck?

Emily’s answer is that Cheri did go back to bed. “Yes, but she’ll be helping Daiyu do whatever she wanted to do. Daiyu could get people in trouble with Papa J and Mazu, if they didn’t do what she wanted” (620). Okay, but the young girl cannot drive. Why is she defenestrated that night well before the dawn trip to Comer?

Confused? I sure am, obviously. If I’m really going to try to solve this novel before the Big Reveal, I’d better sketch a time line that has at a minimum the deaths of Allie Grave, Daiyu Grave-Wace, Jennifer Wace, and Rusty Anderson in the right sequence (to prove that Nicholas Delaunay killed them all — in service to Jonny Rokeby, Heroin Dark Lord!) and Mama Mazu’s age at the time of Daiyu’s birth.

I tack this speculative wild ride on to the Part Six latch discussion, though, as a possible third latch connection between its opening and closing chapters. At Robin’s release, she suggests sardonically Jonathan Wace cried when he pulled the trigger that killed Kevin Pirbright. In the opening section in parallel with that comment, the recording of that same Kevin Pirbright in garbled language says he was going to be meeting with someone tied to the events surrounding Daiyu’s disappearance, drowning, or death by other means. That person has to be suspect number one in his murder — and, Mazu or Papa J being unlikely meeting guests, I’d guess Cheri Gittins or, my stand-by, Nicholas Delaunay. I have no problem imagining the Royal Marine officer killing Allie then Kevin for investigating, chipping the Delaunay name off the apartment wall, and making a stealth exit; Cherie not so much, right?

Regardless, the Part Six latch is sealed with the three connections of beginning and end: Strike in car, the mentally ill Uncle Ted and PTSD Robin, and the Kevin Pirbright talks.

The Turn: Part Six has twelve chapters which, as an even number, has no natural center, a chapter with as many before as after it. Having used the first three chapters and the last two as our latch, however, chapter 84 now has three chapters before and after it with Strike chapters on either side and two chapter Robin sets before and after them. Let’s assume, then, that chapter 84 is the Part Six turn.

This is a brief and disconcerting piece. Yes, Hattie lets Robin out of the box as it begins, but, as the Season of the Healer Prophet begins, our heroine is in need of more healing than a UHC prophet can provide. Rowena has been broken, full-stop.

Nothing mattered to her now but the approval of the church Principals. Terror of the box would be with her forever; all she wanted was not to be punished. She was now afraid of somebody from the agency coming to get her out, because if they did so, Robin might be shut up in the box again and hidden away… She must comply. Compliance was the only safety (612).

And then things, incredibly, get worse.

She is taken to the farmhouse, up to the attic-nursery and told she must take care of the dying child Jacob, “the most monstrous thing she’d seen yet.” “The child was clearly on the brink of death,” and, Robin realized, she was getting child-care duty so, when the boy died, she could be blamed for it (614). She starts to chant Lokah Samastah Sukhino Bhavantu, “may everyone, in the whole world, be happy,” as she had been taught, in conformity and compliance, but stops herself. Instead she repeats a new mantra: “I mustn’t go mad. I mustn’t go mad” (614). That possibility seems almost a likelihood at the end of chapter 84, the Part Six turning point.

The link with the opening chapters is their focus on Uncle Ted, a beloved man who is losing his mind, too, albeit to dementia rather than because of effective mind-control techniques and physical torture. As discussed above, Strike, Lucy, and Greg are rather at a loss about the best course of action because his condition is clearly deteriorating fast. Strike is just beginning to grasp that Robin will take a long time to recover from her time at the Farm as Part Six ends.

The link connecting the story turn in chapter 84 with the two closing chapters in the Bramble Guest House is Robin’s determination to rescue Jacob. She tells the police during her eighty minute interview to ignore the visible injuries she has and focus on getting to Chapman Farm’s ‘nursery’ before the boy dies. She witnessed Louise Pirbright’s grief and love for her dying son, a mother’s agony about being unable to help her boy or escape with him, and Robin has somehow bottled that maternal love, a token of Christ’s love in everything Rowling writes, to keep herself together.

The Turtle-Back Lines: There are only two parallel chapter sets on either side of the turn-latch axis, the first pair of which added together is only four pages long.

Chapters 83 and 85 are the single pages, front and back, that bookend Robin’s agony in the story turn and are about Strike’s vigil in the car and in Fellbrigg Lodge waiting for her to get to the perimeter break-out spot.

Chapters 81-82 and 86-87 are Robin chapter sets. In the chapters going ‘up’ to the turn, she is almost drowned in the Temple’s pentagram pool because she failed the test for “purity of heart” that Mazu was inspired by the Drowned Prophet to set for her. That not being enough, she is interrogated in a basement room without windows or vents, only a camera, by Jonathan Wace and manipulated into copying out and signing a confession written for her and accepting punishment for her thought-crimes. She climbs into the box, little more than a trunk with a breathing hole, for her eight hour penance.

On the ‘back’ or ‘down’ side of the ring, Robin is with Jacob in his attic nursery, a nightmare shift with a starving, epileptic boy suffering with something like dysentery (did anyone else think of the suffering soul-fragment at the mystic King’s Cross Station in Deathly Hallows?). Unlike the front chapter in which Robin is being questioned, in the back parallel she is the one asking for answers; Emily comes to relieve Robin at her half-brother’s crib and, under forceful questioning by Robin, she reveals who Jacob is, what she knows about Daiyu’s “drowning,” and that Kevin knew all this, too.

The man who interrogated Robin in the front chapter of this set about all her failings and who sentenced her to confinement in the box, Papa J, appears on the back side as well, in which chapter he greets her with a cheery “Artemis, are we friends again?” He then gives her another horror-inducing task to endure as proof of her penance and recover: spirit bonding with his son, Taio. The prospect of this rape of her body after the assault on her mind, with the conviction she has that Strike is waiting for her at the property perimeter, gives Robin the adrenaline to attempt her escape.

[Marion Huxley, a woman Robin branded a “fanatic,” a person with whom one could not reason, told Rowena at the end of Part Five that Daiyu was coming to “sort her out.” I suspect now, having read Part Six, that she had that inspired understanding via hints from Becca, who, as a church Principal, was probably aware of the Drowning Prophet Manifestation being staged for Robin. I was delighted that Marion was in the women’s dormitory bathroom when Robin made her escape. (That last name, though, suggestive as it is of Aldous Huxley and his most famous novel, Brave New World, makes me wonder if she is not the former resident and UHC believer who has returned to Chapman Farm after many years. Is her crush on Papa J because he ‘increased’ her in a Retreat Room when she was a much younger woman?)]

Conclusions: Meaning in the Middle

I’ve tried to include a summary to each of these discussions of Part structures in Running Grave which answers the question, “And why are we doing this ring-reading again? Before we get to the finish and can see how the Parts align?” I think there several reasons, realities that are becoming more apparent to me as I enter the third week after Strike7’s publication.

Most obvious, in not rushing right to the finish and by writing up my thoughts after each Part, I’m able to notice things on my second and third passes through a chapter bundle that I never can see on a hurried reading straight through. I read the Part, I chart it which requires a review of every chapter, and then I try to identify the ring elements in that chapter set. Writing up the thoughts are an equivalent of a fourth reading. Of course it’s more satisfying and surprising an experience than the thrill of reading whodunnit after a frenetic turning of pages, inevitably ending with the rhetorical question to self, “How did I miss that?” The answer to that question, I know now, is “Because I read it start to finish without more than a brief look up from the page at plot points that were suggestive, hints of clues.”

More important than having a chance at beating Strike and Robin to the solution, though, the charting process insures that at least the structural piece of Rowling’s ‘Shed’ artistry gets its due. I have been asked at almost every talk I’ve given on ring composition, “How do you see all that?” The rude but true answer is “I look for it.” Ring reading, as I hope you’ve picked up if you’ve read the first six of these pieces, seven if you’ve read the analysis of the Prologue, is not rocket science, brain surgery, or skyscraper construction. It’s much at the mental accomplishment level, once you know the sequence and elements, of cutting the lawn or doing laundry. A reader only has to have a fifteen minute introduction to latch, turn, turtle-back parallels, and rings-within-rings and the desire and determination to chart the work to do a ring reading.

The weird thing?

It is a whole lot of fun in the end and a process, while time consuming, is not arduous in any way. I’m re-reading a book as I read it that I’m almost certainly going to re-read and listen to as an audiobook multiple times. By doing this first thing, I not only am sure that it gets done — no one to my knowledge has done any work to chart the Parts of Ink Black Heart or the first four Strike books, though I demonstrated in my first reading of Troubled Blood that its Parts were rings inside the novel’s ring — I am able to see the structural pointers as to what Rowling is really trying to convey.

I take it as a premise that Rowling is trying to do more than entertain her global audience of readers, though certainly she doesn’t neglect to write an entertaining thriller which engage and enthrall us all. She does so much that is invisible to her readers, everything allegorical and sublime, of course, but the structural intricacy that few appreciate as well, that I think the assumption that she is delivering covert messages that will subliminally affect all readers and which the careful will experience consciously is justified. Not to mention that she has done this in every work that she has written to date.

Reading the structure of each Part has significant markers for what this covert or under-the-conscious-threshold meaning may be. This message or between-the-lines teaching is nothing as obscure or sublime as the Estecean inside-is-bigger-than-the-outside meaning of the Circle per Eliade (listen to the lecture I gave several years ago to explore those symbolic depths); this is straight-up, ‘find the ring’s turn and ponder what its freight of meaning may be.’ As Mary Douglas explained, much more often than not, in a ring composition ‘the meaning is in the middle.’

As noted above, the turn of Part Six is a pretty tough chapter for the principal character involved and the sympathetic reader; in chapter 84, Robin is let out of the box after eight hours in a tortuous physical position and an at least as excruciating (literally, ‘straight off the cross’) mental confinement. It’s worth repeating the paragraph quoted above that summarizes Robin’s state as she finds her bearings after being released by Hattie:

Nothing mattered to her now but the approval of the church Principals. Terror of the box would be with her forever; all she wanted was not to be punished. She was now afraid of somebody from the agency coming to get her out, because if they did so, Robin might be shut up in the box again and hidden away… She must comply. Compliance was the only safety (612).

In a few weeks of sleep deprivation, low-quality and quantity calories and nutrients, immersive indoctrination and group experiences, chanting in unison words one cannot understand, mindless, hard labor, and manipulative approval in sequence with punishing criticism, Robin has been reduced to this: a conformist zombie who wants nothing more than to please authority and not be punished. The meaning of this moves from the borderline vacuous take-away lessons to a profound indictment of the naive way we live our lives qua postmoderns.

The easy way to read this chapter is, “Boy, am I glad I would never join a religious cult! They’re bonkers!” That for most of Rowling’s audience would be to confirm the narrative they have already of believers as stupid by definition, especially if they are critical of the prevalent regime of ideas (the Idolatory Isms: we’re against materialism, capitalism, authoritarianism, rationalism, spiritualism, et cetera). There’s much than a touch of smugness involved because the end of this reading is “I just have to continue to think the way I think and avoid the things I already avoid.”

It’s also not a very careful reading of Running Graves. The take-away position of readers who feel only confirmed by Robin’s experience inside the UHC (“No Scientology, Latter-Day Saints, or Opus Dei for me!”) is the starting-point of Strike and Robin’s thinking about her vulnerability to mind-control techniques; Strike says out loud that Robin isn’t stupid, meaning she won’t be sucked into a cult experience even when neck-deep in it and without escape options.

Rowling’s message, I think, is that we al live in the box of the prevalent metanarratives, choose to live there, and, as in the twice repeated passage, dreads being ‘liberated’ from those opinions because the authorities will only punish her more for ‘escaping.

Her hope may be that we get what she is saying in a not so subtle allegory about the mind-control regime within which we all live. How many friends do you have that self-censor, choosing to live a life of private opinions, lest their Christian faith, objections to the political and economic regimes, not to mention disagreement with the prevalent transgender madness become public and they lose their position, privilege, and comforts? I have plenty of friends who live as cowards in this fashion and quite a few, too, who believe that the way we’re supposed to think is the only way to think, any disagreement being a sign of what a niece told me was best described as “ignorance, unkindness, or imbecility.”

I think this is Rowling’s target audience. It’s not an accident that she has Wace demonstrate that he has Trump Derangement Syndrome, just as Rowling had; she’s saying the Shadow Casters in Postmodern Plato’s cave are less interested in the beliefs they instill in the cave dwellers today than that they control their minds.

She shows very soon after Robin’s release, if I’m right in this reading of the Part Six ‘meaning in the middle,’ the process of freeing oneself from this indoctrination, the figurative mental box, and fear of the literal box. Robin’s first steps to recovery come in Jacob’s attic, her King’s Cross in which there is no Dumbledore, just the wasted Voldemort soul fragment. Robin demonstrates the choices and decisions confronting anyone interested in living with the truth rather than what we are taught to think.

The information [from the floor newspapers in the attic] Robin had been denied for so long, information unfiltered by Jonathan Wace’s interpretation, had a peculiar effect on her. It felt as though it came from a different galaxy, making her feel her isolation even more acutely, yet at the same time, it pulled her mentally back towards the outer world, the place where nobody knew what ‘flesh objects’ were, or dictated what you wore and ate, or attempted to regulate the language in which you thought and spoke.

Now two contradictory impulses battled inside her. The first was allied to her exhaustion; it urged caution and compliance and urged her to chant to drive everything else from her mind. It recalled the dreadful hours in the box and whispered that the Waces were capable of worse than that, if she broke any more rules. But the second asked her how she could return to her daily tasks knowing that a small boy was being slowly starved to death behind the farmhouse walls. It reminded her that she’d managed to slip out of the dormitory by night many times without being caught. It urged her to take the risk one more time, and escape. (618)

And she does just that, of course. My suggestion is that “outer world” in this passage is best understood as Rowling’s rewriting of the Cave allegory. Just as in Socrates’ telling of the tale in Plato’s Republic, the UHC members are certain they will die if they leave the cave and only the idea-shadows on the wall unique to the Wace temple-cavern are real. The author is calling us to escape our mind-traps — and we all have at least of our defining ideas from authority and convenience, getting-along,’ rather than reflection on our experience and from conscious decision making (think CBT awareness).

I am as confident that, if asked, Rowling would say that Robin’s experience in Running Graves of a world in which “the language in which you thought or spoke” was monitored, regulated, and met with commensurate rewards and punishments for degrees conformity or non-compliance had nothing to do with her experience of defending the rights of biological women to safe spaces. Of course she has done not one interview to promote this book, a first in her career, and, barring personal crises in her family of which no one outside her inner circle is aware, my guess would be she does not want to answer that question (as she had to do repeatedly with Ink Black Heart).

More on this if the next three Strike7 Parts support or undercut my working thesis. I’ll close, though, by saying that Rowling has always worked to puncture our attachment to the cultural metanarrative, to foster skepticism towards what everyone accepts as true unthinkingly, in that respect being right onboard with the defining metanarrative per Lyotard of our historical time. This book, through Part Six, at least, seems an especially vivid assault on the surety with which the secular Puritans of our times police everyone’s thinking.

On to Part Seven!

I won’t comment on all the structural details other than to say Rowling is masterful. The attention to these kinds of details and subtlety that many never pick up but contribute to her works is beyond my understanding and I am in awe.

It is fun to read your predictions on the whodunit while I know the answers. To see which clues you have picked up on that are right and which are wrong is a great read.

Your assertions at the end of this post were exactly what I was thinking as I read this book. There is such smugness in the politically correct, cancel culture, censorship madness we find ourselves in. Those that think certain political parties or faiths are in the wrong and brainwashed don’t realize how much they are part of the groupthink they accuse others of. Their false superiority and belief in their own higher morality in all matters boggles my mind sometimes. Rowling’s Twitter wars regarding these topics and how others view her really are represented in how she narrates this book and these subject flowing throughout.

.

Oh, and you were pretty much right on the money with the Daiyu events, just evaded by the elusive killer!